With the final digitisation of Rip It Up now online at Papers Past, two regular contributors explore the back pages of the magazine’s second decade. A sequel to “Every issue felt like the last issue,” The Spinoff, 17 May 2019.

Rip It Up 102, January 1986: Alannah Currie. - Rip It Up Archive / Papers Past

Simon Grigg: Alannah Currie is the first cover of 1986. New Zealander musicians doing well internationally was a big story then. No, make that, it was an almost unknown story in 1986 unless you had an Enz connection.

Chris Bourke: The magazine had launched in 1977 with a two-part interview of Mike Chunn divulging Split Enz’s bleak life in London and on the road.

Simon: A woman from New Zealand was next level, from a country where women still struggled to get their heads above the male-defined musical parapet. That made Alannah’s story a very big deal and yet, incredibly, very few New Zealanders had heard the news that she was proudly ours. George Kay profiled her in March 1983 in Rip It Up but the mainstream media happily ignored the fact that one of us was in one of the biggest pop bands in the world, The Thompson Twins.

So Murray’s cover was important, and the story, by the much-missed Duncan Campbell who had long championed Alannah, was fun, funny, and poignant: “Those who saw the video from last year’s Into the Gap tour will recall a scene on the tour bus where Currie breaks down and tearfully narrates through shattered mascara the pressures of being A Name and A Face, recognised and constantly pestered, unable to go shopping, dancing, do things the anonymous take for granted.” (See also: Brave Words & Assorted Biscuits, on The Chills, by Russell Brown, December 1987)

Rip It Up arrived in a very barren environment in 1977. That was the year when RIANZ declined to hold an awards ceremony because there were not enough local records being released (the same reason Rip It Up’s predecessor Hot Licks rotated the same handful of local acts in its issues – that was all we had). This meant that RIU was dominated by international fodder for the first few years despite a growing number of local single reviews and supporting stories.

Local music journalism was a tough job, but Murray was determined to encourage it and as the indies rose so did the opportunity to do that, to write seriously about local music. The briefly – as in only lasted a couple of issues – great Rip It Up Extra [1980] was just that. Hiring instinctively talented writers Russell and then Chris (as editor, 1986-88) was a very big part of that. It changed the game almost overnight and nowhere was that more evident than in thoughtful, generous and important editorial features like these.

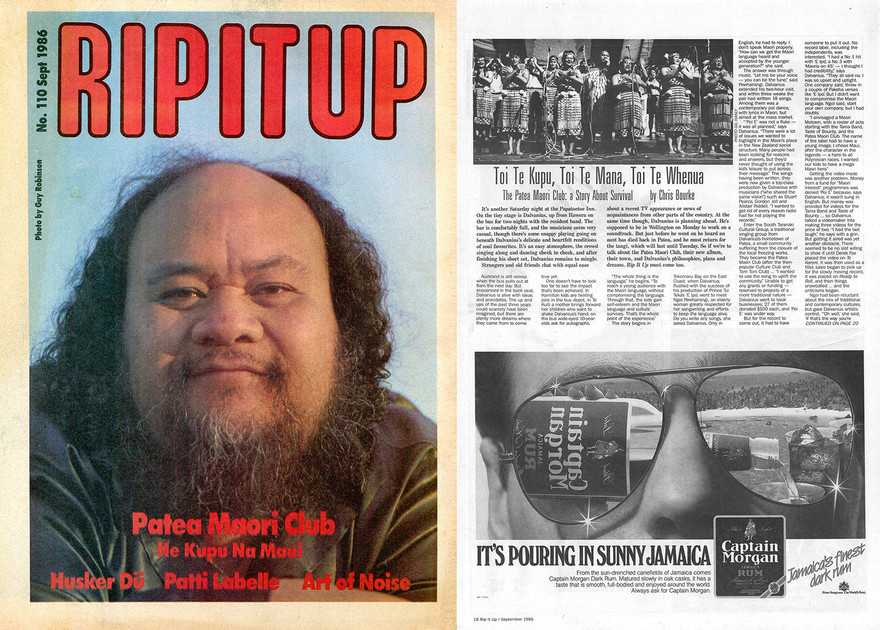

What mattered here, too, was the magazine’s jump into Pacific Aotearoa, especially after Chris took over. The magazine had been very much a white, male rock fest in its earlier years; noticeably, this began to change. Chris’s stories, which underlined the role RIU played not as a document of social and cultural change, but as a contributing force to that, were very incredibly important for that reason and people noticed. Both writers gave RIU some of its best music writing ever.

“I came away feeling that if there is any mainstream ‘movement’ in New Zealand that’s alive and developing, it is the Māori and Polynesian music of which these four bands, with the Pātea Māori Club, represent the leaders,” wrote Chris in August 1986.

Rip It Up 110, September 1986: Dalvanius. - Portrait by Guy Robinson, Rip It Up / Papers Past

Confidence. Confidence, maybe sometimes bordering on endearing arrogance followed the editorial leap of the mid to late 1980s. Whereas the writers and the people they were writing about in the early days of the magazine were often hesitant as they attempted to bypass the cultural cringe that partially defined us in the early days, that disappeared as the decade progressed. Writers with firm opinions like the pithy and often hilarious Kirk Gee: “You really don’t have to be too clever to do this ‘rock interview’ thing, and lord knows I’m not, but even I can tell when things are getting hopeless. Case in point: Gibby Haynes of the Butthole Surfers has just reclined on a luxurious Capitol Records conference room couch, inhaled a good-sized fatty, and is now explaining through a cloud of pot smoke how the Turtles played at the White House. I understand sensible conversation is now over in this interview ...”

S.P.U.D.'s Matthew Hyland who, at times, took few prisoners: “Ice-T may well be the Tom Jones of rap. That isn’t meant in a derogatory way, it’s just that he takes his stage persona all the way, to the point where you have to be totally seduced or left out altogether. And as he’s got some exquisitely brutal music and has the ability to make evil rednecks turn purple with apoplectic rage, anyone would be a fool not to take the first option.”

Or, the just fabulous Kerry Buchanan whose singles, book, TV and film reviews became appointment reading until he scarpered over to Real Groove for his regular hip-hop column and a guest appearance in Shortland Street. Nobody managed to fire up the letters page like Kerry: “For years now I’ve been checking out Kerry Buchanan’s Singles review column and recoiling in horror at his shocking taste. In your July issue, he surpassed himself by trashing the Velvet Underground (simultaneously praising Andy Warhol and his films?). I rest my case; this man’s taste buds should be declared a dangerous zone and the public protected from them.”

See more: Ramalamadingdong, Bigger Than King Kong, by Kirk Gee, November 1989; Underneath What, by Donna Yuzwalk, April 1990; Public Enemy, ICE T, MC OJ & Rhythm Slave, by Matthew Hyland, August 1992; Global Village, by Kerry Buchanan, August 1994; Have You Ever Been to Electriclarryland? by Kirk Gee, July 1996

Chris: Going to visit Kerry Buchanan at Rock & Roll Records on Fort Street, to pick up his hand-written singles columns, was one of the highlights of editing Rip It Up. He also wrote the occasional feature such as one on The Cramps, or a bizarre 10-minute phone interview with James Brown, when JB was losing the plot. Also the reliable veterans who dropped in their copy or used a 10c stamp: George Kay, Peter Grace, Jewel Sanyo, Peter Thomson, plus Russell Brown in London, and Kerry Doole in Canada. And Chad Taylor, stylish man-about-town and assistant editor in 1988-90. He laid out his own features with elegance, and was the first Rip It Up contributor to publish a novel (Heaven), for which he was profiled by Donna.

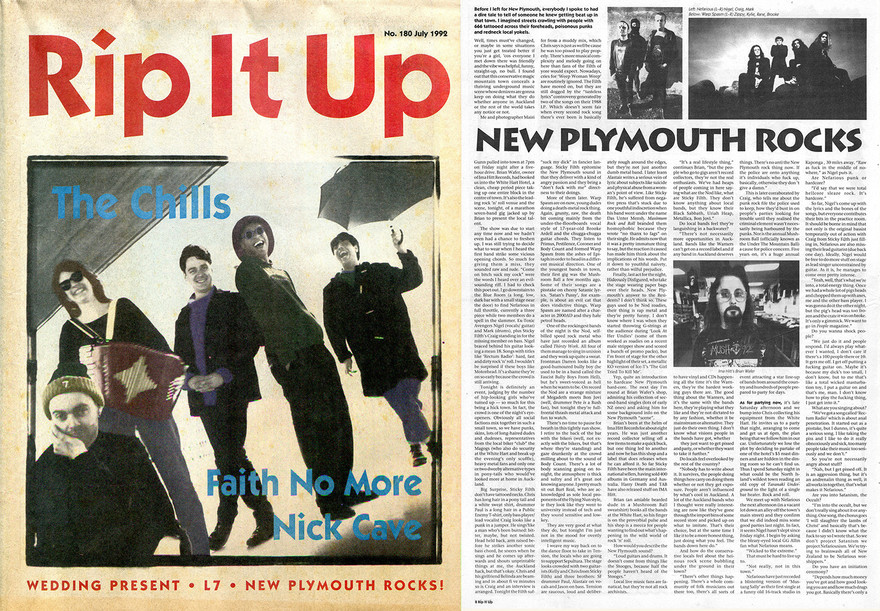

Rip It Up 180, July 1992: The Chills. - Rip It Up / Papers Past

Simon: I don’t think Donna Yuzwalk and I shared a single second in musical taste, but I liked her writing. There is almost an industry to be had in documenting Donna’s five years at Rip It Up. Not only did she dominate those years as a writer, she redefined what was once a male bastion, in part because much of the music she wrote about was heavily testosterone-filled. Pick any issue from her first review – appropriately of a metal night at The Powerstation – to her resignation as assistant editor in August 1994 to witness an entertaining journalistic force of nature. I liked the intro to Belinda Todd (the Nightline host shared a cover with Push Push) in March 1992: “Demented production values aside, one of the most prominent reasons for the show’s success has been Miss Todd, the carrot-topped vamp who upstages her guests merely by her presence, for that is the quality BT has by the bucketload, that and one of the loudest, shortest wardrobes in town.”

Or Donna on Robert Smith, in April 1992: “Robert Smith may not personally have ever sat on a gravestone at midnight sucking on a bottle of red wine whilst straining to read Rimbaud by the light of a match, but that’s the kind of behaviour his music encourages.”

The Cammick era took us from a year when the New Zealand music awards were cancelled because of lack of releases to a year, to – two decades on, almost to the month – when a New Zealand artist hit No.1 in the US. The magazine, and Murray’s instincts, in large part drove that change and that will forever be a gilded part of his legacy. He taught us to like and value our own artists without cringe in a period when our mainstream broadcasters largely ignored and derided the sounds we made and the people that made them.

Chris: There are so many stories by Donna where the humour and flair still sparkles. She explores the New Plymouth scene in July 1992, and has an empathetic profile of Jan Hellriegel confronting the star-making machinery in September 1992.

The magazine refreshed itself, thanks to Donna’s features and Murray’s enthusiastic coverage of the hair-metal bands. They’re treated with respect, while enjoying how ridiculous they are. Push Push, Dead Flowers: they provide good copy and great photos. It’s a shame that the printing in the early 90s was so woeful: blurry colour pages and inky, smeared black and white pics. Desktop publishing had arrived, which allowed for endlessly creative, constantly changing layouts: some knock-out pages and some duds.

Murray was also championing new writers, such as Troy Ferguson, Greg Fleming, and Matthew Hyland – who was now at university, and playing in S.P.U.D. – was appearing more regularly. Matthew is very funny reviewing a gig of Johnny Cash in March 1994.

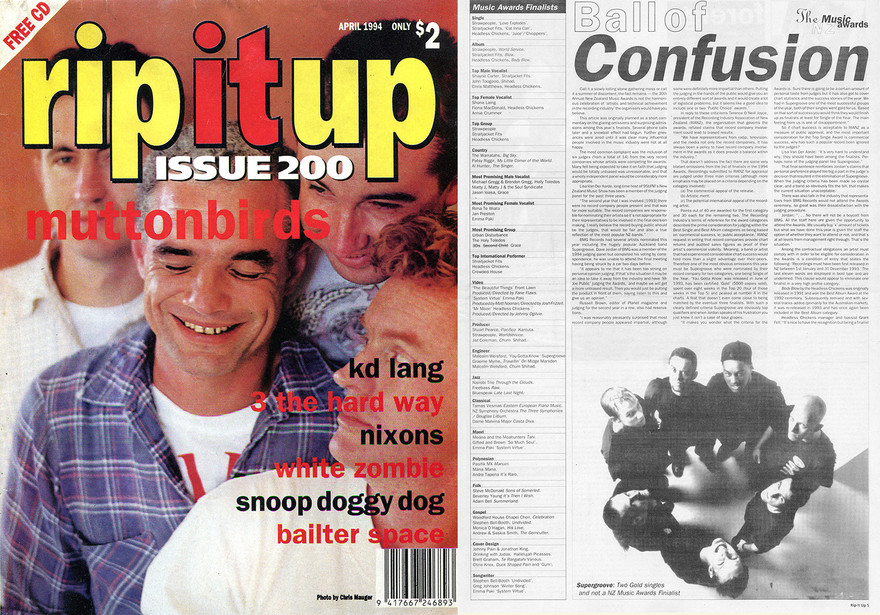

Rip It Up 200, April 1994: Mutton Birds. - Photo by Chris Mauger, Rip It Up / Papers Past

The biggest change comes in April 1994. The purchase by Liberty Press means that after being free for 17 years there’s suddenly a cover price ($2). But that means the cover is on glossy paper, and the colour pages inside also attract mass-market advertising for fashion and shoes.

When John Russell began contributing, he had been producing his own fanzine in his teens. In that April 1994 issue, John wrote a long, excellent piece of well-researched journalism, on problems with the New Zealand music awards.

There’s also a more consistently humorous tone to the mag now, which could be very earnest (and I plead guilty). Harry Ratbag and Shayne Carter had contributed satirical columns in the 80s, and now satire is back, with Boggles Ryan, Elvis Slag, and Lionel Tap.

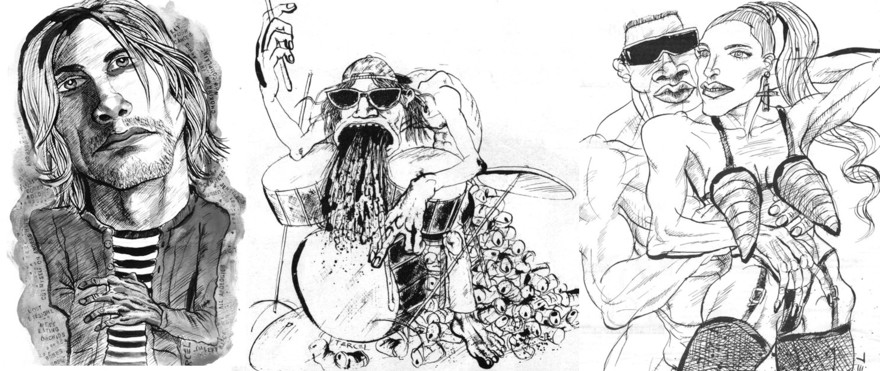

I’d forgotten about the brief wave of cartoon portraits that appeared in 1994-95. The identity of the illustrator, Tercel, is now forgotten, but his work really adds a swagger. There was always a problem with illustrators: we wanted them but couldn’t afford to pay them.

Cartoons by Tercel, 1994-95. - Rip It Up / Papers Past

Simon: In December 1996, one of Murray’s very best discoveries, John Russell, lauded the man who had made that final jump in the US: Pauly Fuemana. John wrote a terrific, dense overview that caught the maelstrom Pauly was in as no other writer had.

John, one of a fine new class-of-the-90s that included Mac Hodge, Shirley Charles, John Taite, Jesse Garon, and Bronwyn Trudgeon, first wrote for the magazine as a singles reviewer and his regular singles columns continued the magazine’s fine history of pop-sensibility with irreverent humour, something that would spark up the letters page at times as bands and fans objected. In his first column, John told us he was far too single to understand Dribbling Darts’ four-track EP of troubled relationship stories. That came with the big smile that sparked much of the last decade of Cammick Rip It Up ownership and lightened the burdens Murray had to carry at times. It’s no wonder he and John remain close.

Rip It Up 204, August 1994: Jordan Luck. - Rip It Up Archive / Papers Past

Chris: As with Donna, there are countless stories by John that deserve re-reading. He has a cheek that gets interviewees onside, making otherwise pro-forma phone interviews crackle. He made Shirley Manson laugh when, in person, he asked if her husband was getting lonely back home. That’s cheek. But he also rolls up his sleeves for lively festival features (Mountain Rock at Woodville, February 1995; Strawberry Fields at Raglan, April 1995, in which he describes Diesel as being “slick like snot”). And he wrote important, and compelling, industry features. (A roundup of independent New Zealand producers, August 1994; New Zealand musicians overseas, October 1995).

The Big Day Out years were mutually beneficial for the magazine and the festival. In February 1995 there are three pages of tight text, followed by four pages of energetic photos of musicians and fans: they’re like a celebration of the readers. The years after the cover price also bring a regular, substantial letters page: not adolescent indulgence but informed outrage at the content.

Rip It Up 239, July 1997: Bic Runga. - Rip It Up Archive / Papers Past

In Winter 1997, Rip It Up marked 20 years with several issues featuring major interviews with key people from its era: Neil Finn, Chris Knox, Simon Grigg, Roger Shepherd, and a cover interview with Bic Runga (July 1997). In a year, the Cammick era would be over, and while there were many good features afterwards, and talented editors, the unique voice he nurtured was dispersed.

There was always wisdom and creativity in Murray’s editing, and plenty of humour in the 90s. His editing philosophy should be copied by every other magazine: reliability and surprise. Keep the readers coming back with consistent, credible copy, but surprise them every now and then with something that has required extra effort. So the readers aren’t taken for granted.