Emerging from the chrysalis of The Book Of BiFiM and lasting a little over two years, Monitor magazine reflected an Auckland that was increasingly confident and flash. While remaining part of bFM’s umbrella operations, Monitor set itself apart from the radio station in a way The Book Of BiFiM never attempted.

MC OJ and Rhythm Slave on the cover of Monitor, May 1991

It championed rap over rock, enthused about fashion, models and blockbuster art exhibitions, had wine and theatre critics, and approached the world with a dark, acerbic humour. Monitor was both impressive – it featured some fine, informed writing and photography and pioneered the glossy free magazine – and annoying: a brattish, laddish, sneer ensured it was often dismissed as a hipster boys’ club. For better or worse, Monitor could be seen as a template for Pavement, the hugely successful and extremely controversial style bible.

There were many connections between BiFiM and Monitor which mean there was a natural evolution between the magazines, says Robert Southon, a contributor to The Book of BiFiM from its 1985 launch, and bFM’s programme manager in 1989. But, he adds, there was also a key sense in which Monitor marked a break:

“The decision to change the name from BIFIM to Monitor at the end of 1988 – much disputed at the time – along with the further distancing of the content from the radio output, were symptomatic of a period when people like station manager Simon Laan aka Nick D’Angelo were aggressively pursuing goals, often marketing-led, that were arguably tangential to the station, while others, like me, saw the station as losing its on-air focus and needing to succeed by, first of all, sounding good.

“This issue scarcely got aired in the magazine or on the radio, but it was intensely fought over at bFM and I think was key to the way Monitor went.”

Monitor’s first issue was published in February 1989; on the cover was an image from Vincent Ward’s film The Navigator. The cover signalled the drive for a broader arts approach, already started under BIFIM, had gained more ground over the alternative music content. Meanwhile, in that first number, virtually the only reference to bFM’s on-air sound was the programme schedule hidden towards the back.

Editorial page, Monitor, March 1990.

Visual art often featured on the cover of Monitor. In September 1989, it was Picasso, linking to an exhibition then on at the Auckland City Art Gallery. The issue also features an interview with Bone People author Keri Hulme, possibly one of the last she gave. There is also a sense that rap is the new rock’n’roll, both in the coverage given to New Zealand and US rappers. A double-page spread that promotes a cassette-only release of local rappers, AK ’89: In Love With These Rhymes; the spread briefly profiles each of the rappers involved and states the cassette is available to order only via mail order. AK ’89 is both a follow-on from and riposte to AK79, the pioneering New Zealand punk compilation issued by Ripper Records in 1980 (plus a witty nod to the Flying Nun compilation In Love With These Times). Recorded and issued by bFM, this suggests the station was, at least briefly, thinking of setting up a record label.

It’s unlikely many were impressed, as AK ’89 seems to have been almost totally forgotten. Still, it’s inspiring to see Monitor getting behind what was the most exciting youth music then being created and acknowledging Auckland’s Māori/Polynesian youth.

Gluepot listings, Monitor, March 1990

And get behind rap they did: Nick D’Angelo’s monthly column ‘Pump Up D’Angelo’ gave Auckland’s wannabe Rick Rubin space to comment on the fledgling rap scene (he notes how Upper Hutt Posse, performing in Auckland, apparently announced from the stage “Samoans go home” – how to win friends and influence people ...). D’Angelo also served as Monitor’s version of Metro’s Felicity Ferret, bitching about those he had run-ins with, spreading scurrilous gossip, dismissing Wellington, bemoaning his lack of a love life/fame. Other columnists sometimes followed suit: cynicism, sarcasm and a belief that they were hipper than everyone else flowed through Monitor. But there was also plenty of good writing. Initially Flying Nun artists still got a look in: Chris Knox is remarkably open about his work in a lengthy Q&A while Martin Phillipps boasts that Slash Records paid more for The Chills than they did for Los Lobos or Violent Femmes.

Subscription advertisement, Monitor, May 1990.

“I’d been bFM programme director and news editor and then had a stint as mag editor,” says Paul Casserly, the editor who transformed BiFiM into Monitor. “When it was decided to change the name to Monitor, I’m unsure if it was my idea or not, but I was definitely into the change. I recall there was an attempt to make it bigger and ‘better’ and there was some resistance to that. We always felt slightly outside of the mainstream or ‘serious’ journalist circles – we were making it up as we went along. I certainly felt like I was learning how to do stuff more than doing anything of importance. I’m probably proudest of profiling some cool people and helping some good writing and graphic talent get into print. It was a blast and I’m ever grateful for the opportunity and memories.”

By 1990 Paul Casserly had moved on to a stellar career in media and pop music (Strawpeople) and Michael Lamb, formerly editor of Craccum, took over as Monitor’s new editor.

“As the official mag of bFM we supported the station in any way deemed useful: ad crossovers, programme listings and all that functional stuff,” says Lamb. “It wasn’t too prescriptive or formal and for most of the content it was entirely up to me to do whatever the hell I wanted. I soon got to know who the regular contributors were and managed to persuade most of them to carry on under my auspices. Like Francis Hooper from World. He had a deeply provocative – some might say disturbing – take on fashion which I loved.

“I took my cue from contributors like that really, together with my own leanings towards a sort of post-punk attitude to things and tried to inject a lot of humour into the mag. Paul leaned more toward the uber-cool vibe, which was great, so we just added a bit more chaos on top.

“We had Greg Fleming, Oscar Kightley, Simon Coffey, Matthew Tetley-Jones, and Andrew Dubber writing about music; Mark Tierney on television; Peter Shand on theatre; photography from the likes of Fiona Pardington, Deborah Smith and Polly Walker. If anything, my task was to support them in being as edgy as possible.”

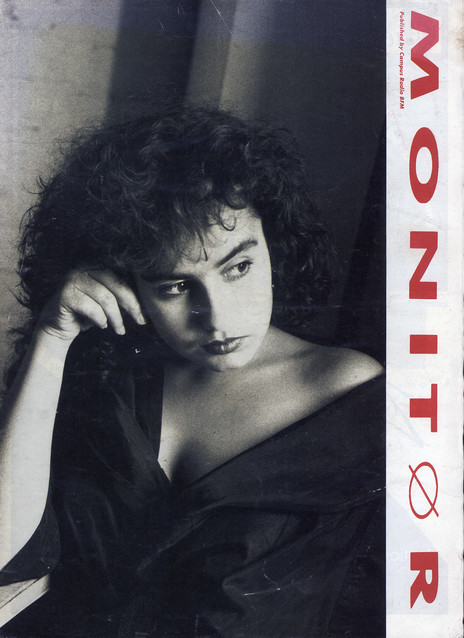

Pagan Records artist Merenia on the cover of Monitor, May 1990.

Monitor went glossy in May 1990 with Merenia on the cover (the young singer-songwriter’s debut album had just been released on Pagan). Columns came to include wine, theatre, print, Wellington, cinema and dancefloor. Art exhibitions and fashion shows got coverage. Local models were photographed. Clubs were championed. An interview with Batman cartoonist Bob Kane finds him dismissing the then-new Dark Knight graphic novel while Glen Campbell (of S.P.U.D.) gets to do a phone interview with Glen Campbell (of ‘Wichita Lineman’), then about to embark on a 14-date New Zealand tour. Caroline Avery’s fascinating Where Have All The Cinemas Gone? looked at many of the suburban fleapits we once spent our Saturdays in (and how those not demolished have been turned into churches, gyms, warehouses etc). The broader coverage attracted advertising from Dr Martens, Levi’s and drinks companies – plus The Gluepot, Real Groovy and other Auckland music institutions.

Ponsonby Blues and Jazz Festival advertisement, October 1990.

Pagan Records advertisement, Monitor, May 1990.

“Music of course was our main beat. In tandem with bFM we were a pretty good guide to what was happening in the independent, alternative scene,” says Lamb. “The mag had pulling power with the music companies so we got offered pretty good interviews – phoners with UK, US, or Australian musicians plus of course New Zealand musos in person.”

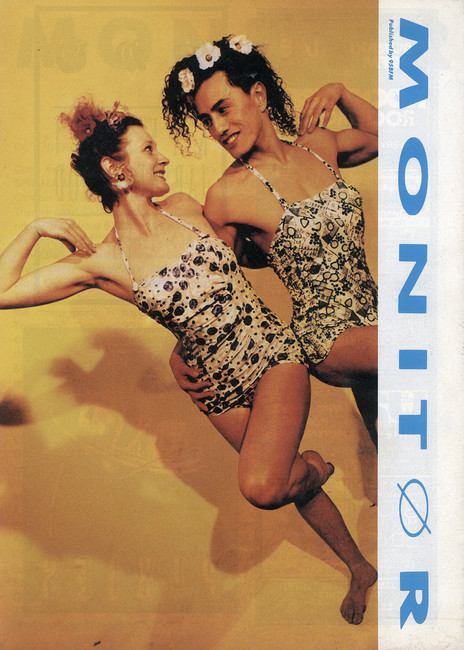

Dancers Shona McCullagh and Taiaroa Royal on the cover of Monitor, October 1990.

Simon Grigg wrote the Dancefloor column; at the time he hosted the only dance-orientated radio show in Auckland. He recalls: “Radio B and their in-house magazine BiFim was firmly stuck in the early to mid-80s indie rock sphere, and both Roger Perry and I had long since learnt to deal with the sneers of the B establishment for playing ‘disco’ on their station. It changed around 1988 though, when a new broom seemed to sweep through the station and names like Mark Tierney, Eddie Chambers, Liz Tan and Paul Casserly not only moved the station towards the sounds that were filling the inner-city clubs but started making records that reflected that in the station’s small studio.

Monitor, March 1991.

bFM Bible, Monitor, March 1991.

“BiFiM was soon replaced by Monitor which reflected the changes too. Paul Casserly and, I think, Liz Tan, asked me if I wanted to do a dance column in the magazine sometime after that with the offer of a contra in advertising for The Siren (which became The Box). At the same time I was writing for it, my wife-to-be, Brigid Eyley, was a photographer around town and had scored a shared darkroom in High Street. For a year or two she was an ever-present lens person in the bars, clubs and cafés of the inner city and her photographs of the likes of Roma, The Siren, DKD and more graced Monitor as on-the-town type shots. They are now a unique document of that time when inner-city Auckland began its decade or so of social fusion, when the races and the cultures of young Auckland came together.”

Funkage - back page advert, Monitor magazine, June 1991.

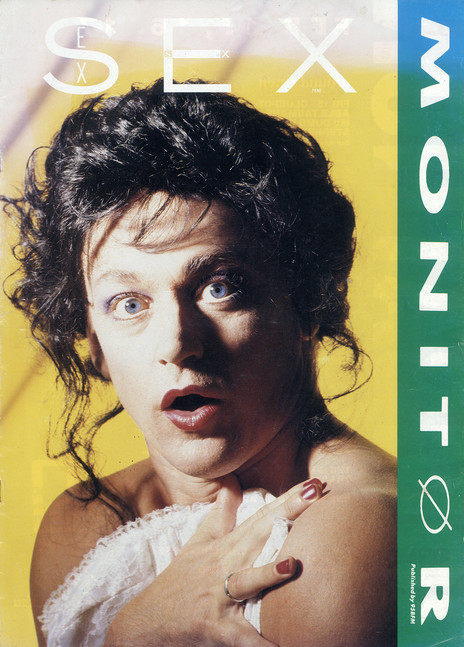

Glossy did not mean bland. Knuckles The Malevolent Nun, a full-page cartoon by Cornelius Stone and Roger Langridge, was designed to offend. Monitor’s printers refused to print one such effort. This and some snide writing likely contributed to Monitor’s brief existence.

“I remember we published an item – it must have been an album review or something – and the bloke who ran WEA Records [Tim Murdoch] spat the dummy and pulled all his advertising,” says Lamb. “I had to go to his office, which was on the top floor of a building up Hopetoun Street, and beg forgiveness because we really needed the revenue. He had this grand office with that clichéd thing of world clocks all lined up in case he suddenly needed to know the time in London, Paris or New York. We got the ads back though.”

Monitor, February 1991.

Monitor, June 1991.

Still, the writing was on the wall, as Simon Grigg recalls. “Monitor simply seemed to try too hard to be hip and never seemed to be able to decide whether it was street mag aligned to bFM or a bitchy inner city gossip and style magazine. Eventually the latter won out and many of the advertisers, us included, decided that we didn’t feel any urge to contribute to a magazine that each issue seemed to belittle what was hot a month or two earlier.”

Robert Southon: “The magazine had gone out on that limb during an uncertain management situation at the station on which it depended. That crisis got much worse – with major disputes at bFM and people on all sides of them leaving acrimoniously in 1989 and 1990 – before it thankfully got better through management reforms and new blood. As Monitor had already slipped through and made its own ‘reforms’, it was on a very long leash for all that time.”

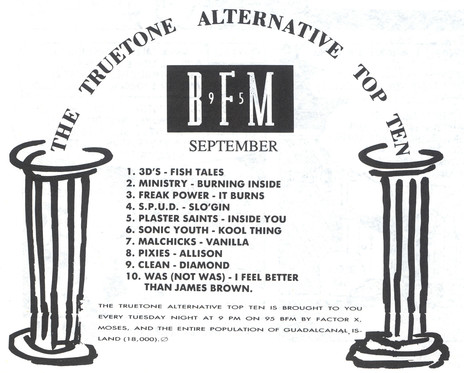

95bFm / Truetone Alternative Top Ten, Monitor, October 1990

Michael Lamb: “Liz Tan took over as station manager. She wasn’t keen on us being out on our own. The clouds were gathering at bFM board level too. The magazine was seen as a luxury bFM didn’t need, getting too far out from under the station’s direct control. Whatever it was, various forces were lining up against us towards the end of 1991. Then it all came to a head when we didn’t have enough ad income sorted for the first issue of 1992.”

Thus Monitor ended with a whimper as bFM axed the January issue.

“The kids would scrum over the copies when they came out around town,” recalls Lamb. “The music shops around town and shops in places like High Street loved it because people came through the door to get a copy so maybe they’d linger and buy something. Journos at the ‘proper mags’ like Metro said they always hung out for the next issue. Being a monthly we couldn’t really break topical stories or get a scoop, but we could be irreverent, subversive, edgy, cool and different.”