Hark Music - The Hamilton Years (1992-1996)

Revolutions can spring from the most innocuous moments. For Grant Hislop, a phone call from his mother in 1992 sparked a series of events that shifted the way New Zealand radio and New Zealand music interacted with each other. Mrs Hislop had found an ad in the paper offering two Hamilton FM frequencies for sale, which caused her son’s ears to prick up.

Grant first became involved in radio at the tender age of 17, not because he wanted to be in radio, but because he wanted to be a rock star. “I thought it would be a great place to make contact with record companies,” Grant remembers.

Grant Hislop

By age 21, Grant was owner/ operator of his own radio station in Tauranga, Coastline FM, which he reluctantly sold after his lease on the frequency expired. With his mother’s discovery of a humble three-line advertisement in the back of the newspaper, Grant was offered another chance to further his personal crusade to get more New Zealand music onto mainstream radio.

At the time, only around two percent of music played on local radio was New Zealand music. “I love local music and I couldn’t understand why we weren’t playing our music. This was a time when the likes of DD Smash were selling lots of albums, but their music wasn’t being played by radio. It was a period where radio people had no relationship with local music people.”

Tetnus

Recognising that something had to change, Grant rushed to Hamilton and negotiated a price. He handed over $2,000 and bluffed that he had the rest. With only three days to find financing, time was of the essence. Fortunately, a family friend came to his aid at the eleventh hour, and Grant moved to Hamilton to pursue the rare opportunity for a second chance and a revolution on New Zealand airwaves. Thanks to the transistor on top of Waikato Hospital, the frequencies only reached as far as the outskirts of the central city. But Grant was undeterred and determined to make it work. He quickly gathered the necessities and people required to set up a successful radio station. After securing investors, he found an ally in 1HZ, the local arm of Radio New Zealand at the time.

Less than a month after his relocation, Grant launched The Rock, which followed the rock-centric programing of Hauraki, but with a distinct twist.

With a temporary studio space obtained, he then set about figuring out what radio format would best suit the town. Official statistics showed that seven percent of locals listened to Radio Hauraki, which was surprising given that its signal could not be accessed in the city. Grant saw a potential audience whose needs were not met by the Top 40 programmes of the day – and therefore an opportunity.

Less than a month after his relocation, Grant launched The Rock, which followed the rock-centric programing of Hauraki, but with a distinct twist. From day one, The Rock was playing 20 percent New Zealand music, a revolutionary act that went against the long held belief that we didn’t want to hear our own music on commercial radio.

Throwing caution to the wind paid off. A year later the statistics spoke volumes, and the advertisers were listening. Grant was able to increase the range of The Rock’s frequency to the entire Waikato before buying 20 frequencies nationwide from the Christian Broadcasting Company and unleashing The Rock to audiences up and down the country. He believes that the reason local music assimilated so well into their shows was because they “sought out music that was in line with the [international] music that was being played. We didn’t try and force feed it. Also, we didn’t create a niche radio station, our music selections were broad. This was the money shot, programming songs that appealed to a diverse audience.”

Local radio stations such as Radio Waikato and Kiwi FM crumbled as The Rock asserted its dominance on the airwaves. His second local frequency was used to appeal to the ever-popular Top 40 sound. It was called The Buzzard, a little hole in the wall venture that became an overnight sensation as other stations shut up shop. Later, The Buzzard changed its name to The Edge, which went to become a bastion of New Zealand’s commercial radio sector.

It is perhaps a surprise to some that two of New Zealand’s most successful radio stations and an ethos that has helped shape our cultural landscape today were born in the backwaters of the Waikato. Hamilton in particular maintains a reputation for having a hard rock listening, swappa-crate swilling, mullet-wearing population. But that is not only a generalisation, it completely ignores the eclectic range of musical styles and bands that were coming out of Hamilton, particularly in the 1980s and 1990s. This diversity of sound greatly appealed to Grant, who continues to have little time for the restrictions of genre in terms of taste and demographics. “It is what it is. I’ve never been into pigeonholing. Growing up, I sang in the National Youth Choir and was a frontman for a punk rock band at the same time. So when people would say to me ‘the Waikato is only Rock,’ I’d think that it was such bullshit and so one dimensional. I looked for excellent songs, and if I liked a band and their music, that was it. I didn’t care about genre.”

During his visits to local pubs Grant found himself exposed to all the Waikato had to offer. “I was really taken by the breadth of talent in Hamilton, I kept finding bands that excited me. I wanted to change the industry’s perception of New Zealand music in general, but I also wanted to put the Waikato on the map.” He began to consider starting up his own recording studio. Grant was aware that the main gripe that mainstream programmers had with local music was that the quality of production was not high enough, but that problem was solved when Grant Hislop met Zed Brookes.

Zed Brookes was a local sound engineer and post production producer working at Tandys, a small studio off Morrinsville road on the southern outskirts of Hamilton. Grant had heard some recordings that Zed had done for Tim Armstrong, a local musician. “I couldn’t believe that such an amazing quality recording had come out of Hamilton,” says Grant, “so I got in touch with Zed and said, ‘I’ll build you a studio if you come and work for me.’”

Tim Armstrong

Selling his shares in his radio enterprise, Grant took the money and with Zed at his side, built The Zoo Recording Studio in a historic building down the north end of Victoria Street.

Like Grant, Zed was an early champion of both New Zealand music and Hamilton’s diverse music scene. “There were all these bands popping out of the woodwork [in Hamilton] and they weren’t crappy bands either, they were really quirky and interesting,” Zed recalls. “Everyone thought that they weren’t going to be played, so there was a sense of “Oh well bugger it, let’s just do what we want to do.”

The main focus for both Zed and Grant was to get an international quality of sound from within their relatively small venture.

The main focus for both Zed and Grant was to get an international quality of sound from within their relatively small venture. “We wanted everything we were pumping out on air to be as good as anything we were hearing from overseas, so that was our main goal,” says Zed. Along with day manager Darren McLean, the trio would spend hours listening to the latest records from around the world, trying to figure out how to emulate or even improve on the calibre they were hearing. To help in this quest, the rudimentary 16-track and analogue mixing desk that had been appropriated from a radio studio was given an $80,000 upgrade.

Initially, the duo would invite local bands to come and record in The Zoo studio as well as putting them on the radio. “It revved the scene up and increased public awareness,” says Zed. “Everyone listened to the radio, and there had always been student radio, so the indie bands had their scene, but if you were a bit more rock or a bit more pop you were stuffed to be honest. It’s not until you get yourself on the radio and are played against overseas artists that you get an idea of where your music really sits. It was quite empowering, and the whole thing just grew, it built itself”

The Zoo built up a reputation amongst listeners and musicians alike for their raucous live-to-airs, which they would record with a live studio audience. Soon, bands from places as far flung as Wellington, the Bay of Plenty, and even Auckland were knocking on The Zoo’s door. The studio was becoming an in-demand, 24 hours, seven days a week business.

As they continued to add to their increasingly long list of artists, Grant realised that they needed to distribute hard copies of the music they were recording, and Hark Records was born. “Distribution was a big thing. We sold direct to 158 retailers and would ship the records straight out of Hark. So we had this full circle operating in this micro-economy. We were playing artists on the radio, setting up gigs for them, and selling records for them. No other independent record labels were doing that,” says Grant.

Although the days were long, they are fondly remembered by all. For Darren, a typical day would begin with a local band coming in to record for half a day. “They would always end up paying with a wad of notes that they had saved up for the big session,” he remembers. This was then followed by one of the bands on their books coming in and working on new music, before doing a couple of radio spots for The Rock. As night fell, a casual sound engineer might come in with another band to broadcast a live to air. Darren particularly remembers sets by Greg Johnson, The Mutton Birds, and Dead Flowers. “I also used to take great pleasure in taking visitors through our studio, like Dave Dobbyn and Supergroove, and telling them they should do their next big album here. They must’ve thought I was crazy,” Darren laughs.

Blackjack

Blackjack were Hark Records’ most commercially successful band. Described by their guitarist Paul Martin as having an “organic rock sound” the legend goes that Grant received a cassette copy of Blackjack’s song ‘Spinning Wheel’ and was so impressed by it that he put it on air immediately. They recorded their debut album, Deal, with Hark, and ‘Spinning Wheel’ charted at No.38 in February 1994. Sell out tours followed and Deal also charted in April 1994 at No.34, selling around 5,000 units. Their second album Kicasso d’Muse was also a big seller but by this time the band had imploded. At this point, The Rock was playing 20% Hamilton music on top of the 20% local music they were already playing.

For the artists signed to Hark Records, it was a liberating experience. “It was all very grass roots, DIY and the attitude was ‘fuck the majors’. I have great memories of the live to airs [a show called the Electric Kitchen],” says Paul. Former musician Andrew Johnstone remembers that “Grant was an anomaly. He didn’t care what scene you were from, he just liked music and had an ear for a good song. Those were dour times for local music and Grant swept in like a breath of fresh air, full of ideas and enthusiasm.”

Knightshade

Grant operated in the space between commercial radio and musicians, and Andrew identified with it. “I wasn’t mainstream, but I wasn’t alternative either. I was just being me.” While Zed was at Tandys, Andrew had been fulfilling his teenage aspiration to record a concept album. It was called The Wallflower. After hearing it, Grant encouraged Andrew to re-record it at The Zoo. It took several months and $30,000. The finished product only sold 220 cassettes, but according to both Grant and Zed The Wallflower was “the album we were most proud of from a creative perspective.” Says Andrew, “Grant was the big picture kind of guy, while Zed looked after the details. They were a good team.”

Andrew Johnstone

Unfortunately this relentless momentum was also haemorrhaging money, something that they could only sustain for so long. In 1996, four years after Grant arrived in Hamilton, both The Zoo and Hark Records went into liquidation. Zed puts the demise of Hark down to overexertion. “Grant wanted to prove that both Hamilton and New Zealand musicians were able to deliver as good as anyone in the world. We were all constantly surprised by the talent, but in the end we couldn’t keep up.” Andrew echoes this sentiment. “Grant was too bighearted. He couldn’t say no.”

When Grant reflects on this time, he says that there are a lot of ‘what ifs’. “Imagine if we had kept going at the high trajectory we were operating at, we could have taken on the world, but sadly we ran out of money at the most crucial moment. I put every single cent into it, and lost my dream in the process.”

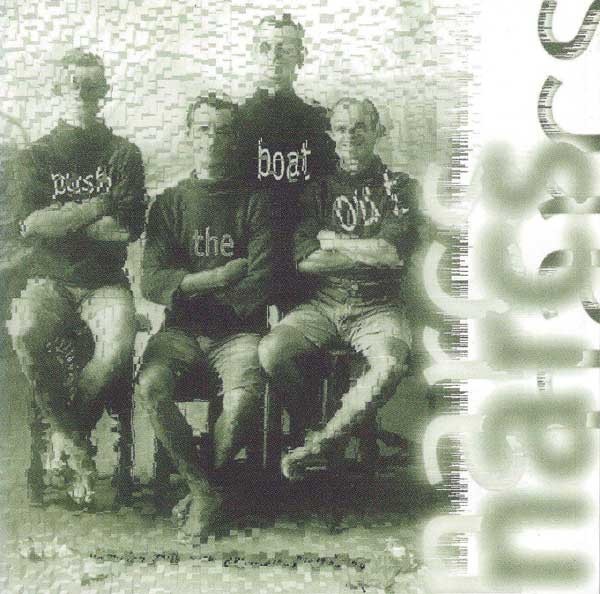

The Narc's final album Push The Boat Out, 1996

After Grant picked himself up, he found radio work in Wellington and went onto manage the likes of Opshop, Goodshirt and Pluto. Grant was also instrumental in setting up Auckland’s Kiwi FM, which eventually went off air in 2015 after a decade of solid support for New Zealand music.

Despite Hark Records and The Zoo Studio only operating for four years, hindsight makes clear how important those years were to the commercialisation of New Zealand music and to Grant himself. Sitting in the audience at the New Zealand Music Awards was not only struck by the respect given to local music, he was also impressed by the multi-faceted nature of the music being celebrated – from Lorde to Sol3 Mio. “It suddenly dawned on me, ‘wow, this is what we were working towards twenty years ago’ – New Zealand music doesn’t need a crusade anymore. The baby is walking.”

Grant’s Top Five Hamilton-era Hark artists

Blackjack: “They had the live chops and songs. Gavin’s voice was fucking amazing.”

Tetnus: “A sloppy, loose three-piece that sounded like a cross between Nirvana and The Smashing Pumpkins and were a voice of their times.”

Jacqui Keelan: “She toured with Tina Turner, and had a truly amazing voice and spirit. Something truly magical happened when she was in the studio.”

The Narcs: “They got critically written off quite a bit, but they wrote great songs.”

Tim Armstrong: “Simply an amazing talent, an amazing songwriter.”

Hark artists

Blackjack

Jacqui Keelan

Tim Armstrong

Knightshade

Tetnus

Dave Williams

Inchworm

Andrew Johnstone

Ritchie Pickett

The Narcs

Bitumus

Fat Mannequin

Inchworm

Julz Cairney

King Biscuit