1968 was the year New Zealand got the blues. The elemental American form, born in the slavery-scarred South, had been around in various guises since the early 20th century. But in 1968 there was such a surge in the music’s global popularity that at least two zines devoted entirely to the genre were launched locally, while homegrown blues exponents commanded features in both the alternative press and the more mainstream pop magazines.

Good Noise - the first of five issues of the blues magazine edited by Colin Morris appeared in May 1968. It covered New Zealand and overseas blues musicians. - Nick Bollinger collection

The zines provide a key to most of the leading local blues figures of the time. They give a taste of the commitment, zeal, and stubbornly held dogmas that characterised the scene. And they offer some clues as to why it didn’t last.

The first local blues zine was started by Colin Morris. It was the Wellington music retailer’s first and final venture into publishing. His marriage had just broken up and he found himself with time on his hands. The blues was booming, thanks to a “British invasion” led by John Mayall whose Bluesbreakers album had made Eric Clapton into a guitar hero and generated a slew of imitators. Though he felt some cultural connection to the British blues, having emigrated from Manchester in 1963, Morris was interested in the music’s African-American roots and would enthusiastically introduce blues-seeking customers at Vanvi’s record store in Cuba Street to albums by southern bluesmen such as Lightnin’ Hopkins and J B Lenoir. When a record company rep asked him whether he thought a 3-LP collection of contemporary urban blues, Chicago/The Blues/Today!, would sell in New Zealand, he replied in the affirmative. The collection was duly released – Colin remembers dispensing 18 sets on the first day – and his status as the “Wellington blues guru” was set.

Good Noise launched in May 1968. In the first issue of the black and white, offset-printed A5 magazine, the masthead lists Colin R. Morris as editor and his friend Lyn Forsberg as subeditor, along with editorial contributors including musician and broadcaster Midge Marsden, local blues expert Bruce Hookham, record collector and ad man Warwick Woodward, and sometime singer, pop magazine editor (Groove) and indie label founder Dene Kellaway. “Regrettably none of them contributed,” Morris says today. “I gave the first copy to Warwick Woodward, who circled all my mistakes – 62 from memory – and sent it back.”

Supernatural Blues Band in Good Noise #1.

Along with a biography of “rediscovered” Mississippi bluesman Son House and an anthropological article on the Evolution of the Blues were profiles of local blues groups Capel Hopkins Blues Dredge and the Supernatural Blues Band, folk singer-turned blueswoman Val Murphy, plus a three-page spread on the third monthly gathering of the Wellington Blues Club, which had drawn 300 people to a Sunday afternoon at the Monmarte [sic].

Capel Hopkins Blues Dredge in Good Noise.

Though Vanvi’s, Morris’s employers, had no special involvement in the publication, a full-page ad in the first issue promoted the contents of the shop’s blues section and offered a nationwide mail order service.

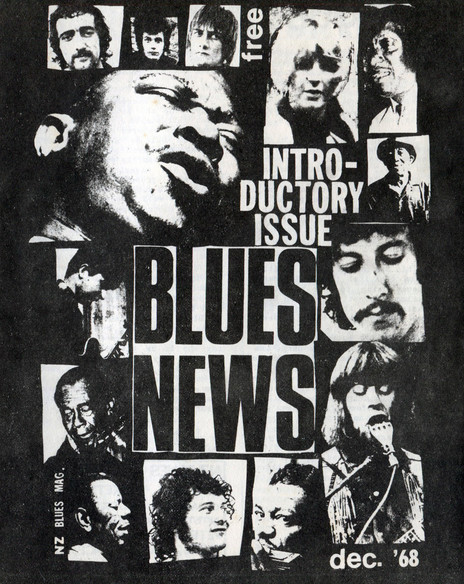

Blues News introductory issue, December 1968. - courtesy David Colquhoun

David Colquhoun was a sixth former at Lynfield College when he launched Blues News, Auckland’s blues mag, in the second half of 1968. The young blues enthusiast had befriended guitarist Henry Jackson who would co-edit early issues, and fellow Titirangi resident Alastair Riddell, then in the process of organising The First National Blues Convention.

For its student founder, Blues News was a labour of love. Colquhoun would take time off school, despite the headmaster’s threats of expulsion, to envelope and post copies of the mag.

Arriving in late 1968, a free introductory issue was partially devoted to promoting the upcoming convention, which would showcase local blues players Pete Kershaw and Tom Crannitch, The Original Sun Blues Band featuring both Jackson and Riddell, and Killing Floor, led by Jackson.

The issue also announced the formation of the Lime Street Blues Club, to be held every Friday at the Wynyard Tavern. Regular artists would include most of the Blues Convention line-up, as well as others including The Mad Dog Jug Jook and Washboard Band, an acoustic outfit that would feature such notable names in the Auckland blues scene as Henry Jackson, Peter Kershaw, Tom Crannitch, Chris Grosz and Robbie Lavën.

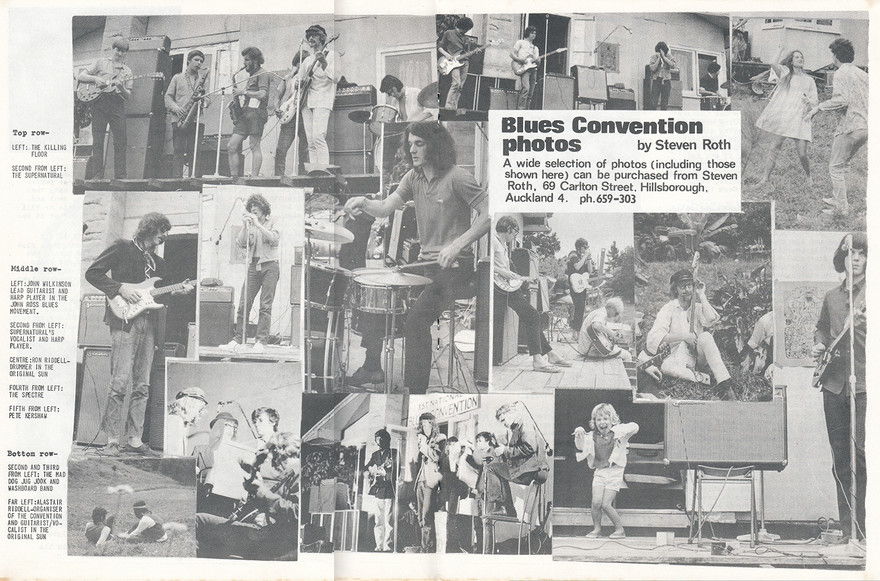

Blues Convention photos in the first issue of Blues News (aka Blues). Among the artists featured are the Killing Floor, the Supernatural, the Spectre, and Ron and Alastair Riddell of Original Sin. - courtesy David Colquhoun

The first commercial issue of Blues News arrived in March 1969 and cost 25c. Though in many ways it replicated the design of Morris’s Wellington mag – stark black and white print with typewriter fonts, Letraset headings and inky reproductions of photographs – Colquhoun, in addition to his own design skills, had the graphic support of Errol McKibben, whose hand-drawn illustrations mirrored the folk-art style of American artist/musician Eric Von Schmidt’s cover designs for popular American roots label Elektra. McKibben’s chiaroscuro portraits of local bluesmen Cranitch and Kershaw give the young aspiring players the sombre look of grizzled veterans.

Peter Kershaw in Blues News #1; illustration by Errol McKibben. - courtesy David Colquhoun

The issue also featured a report on the First National Blues Convention, with a double-page spread of photographs by Steven Roth. David Colquhoun filed a survey of regional blues clubs, covering Wellington, Auckland, Christchurch and, surprisingly, Hawera, population 8000, where the Taranaki South Side Blues Club was reported to be meeting every Friday night. “Hawera is plagued by a dominating interest in pop music,” he wrote. “However a group has now been formed and things are improving.”

Wellington musician Bill Lake provided a dispatch on the Wellington blues scene, judging Supernatural Blues to be the best band in the electrified “Claptonesque” style. The Capel Hopkins Blues Dredge were “less immediately exciting” but more promising overall in their combination of keyboard and guitars, while Gutbucket, with two guitarists “more than competent in the King / Rush / Guy idiom” are the “best modern-styled band I’ve heard in Wellington”. When Gutbucket entered Wellington’s HMV studio the following year to record a single for Dene Kellaway’s independent Tree label – the first time Rick Bryant’s voice would be captured on disc – Good Noise would devote a double-page spread to the session.

Gutbucket in Good Noise #3, 1969; Rick Bryant second from left.

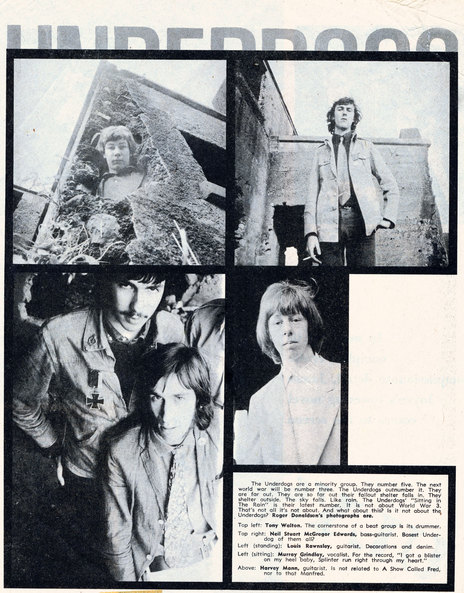

In Auckland, David Colquhoun sat with guitarist Lou Rawnsley who had recently quit The Underdogs, and discussed his feelings about “blues purism” and his approach to the blues. “I used to be like that. It’s a stage you go through,” said Rawnsley. “But then after a couple of years you hear other records, especially the Beatles. They’re really good, I listen to them all the time.”

An editorial preamble to the Rawnsley interview reminded readers: “It should be emphasised that his views are not necessarily our views.” Blues News was purist and unapologetically elitist. “Let’s face it – blues fans in the main are much brighter than the average pop music fan,” an opinion piece declared. Other columns discuss such issues as to whether the saxophone belonged in blues or the standards by which a blues performance should be judged.

Blues #2. - courtesy David Colquhoun

But while local blues performers, and those intent on intellectualising about them, appear to have been overwhelmingly male, it was a female singer, Val Murphy, who honed in on the music’s prevailing theme. “The more I think about it, most of the blues I sing is from the point of view of sex,” she told John Davidson in an interview headed “I Feel Mean and Bitchy”. A successful folk singer with an HMV contract and two albums already out, she had started as a soprano in the Joan Baez mould, but by the end of the decade was turning her focus onto the blues. Davidson asks her about abandoning folk. Murphy says she hasn’t really dropped it, just selected blues from the wide array of folk styles. “The rest of it is so pseudo, the sweet stuff, the nice stuff. I don’t feel sweet and nice, I feel mean and bitchy. And this is why I like singing blues.”

Blues #3. - courtesy David Colquhoun

Towards the end of interview Davidson rephrases the question and Murphy reiterates her answer. “I told you, from folk music I selected blues because now I feel as though I can sing it. Before I knew I didn’t have a show being a soprano, and not really knowing the facts of life, not really knowing them.”

The blues was getting coverage in the mainstream pop press as well. In 1967 Teen Beat had already devoted a full page to “New Zealand’s best rhythm and blues group”, the Christchurch-based Chants R&B, on the eve of their departure for Australia.

Fortnightly pop paper Groove introduced a “Blues Corner”, covering groups such as the Supernatural Blues Band and events including the First National Blues Convention.

The Underdogs go "hip" in Playdate, just after the release of 'Sitting in the Rain'. - Roger Donaldson/Playdate

One issue of Playdate devoted a stylish double-page spread to The Underdogs. In another, Louise Warren reported on a Friday night visit to Auckland’s Underground Blues Club where she was moved to ponder: “People don’t want to sit around listen to a three-minute guitar solo or digressive drum solo … Or do they?”

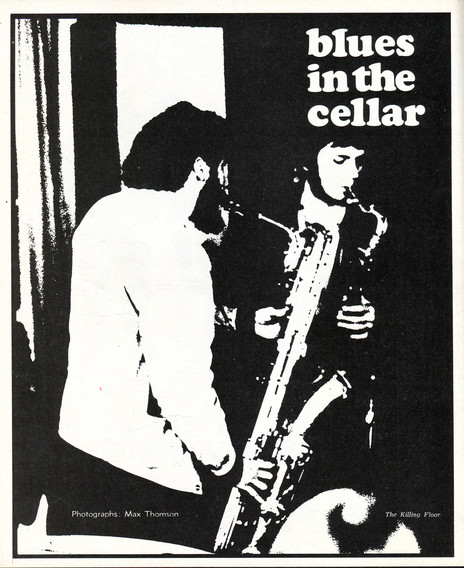

Blues in the Cellar, by Louise Warren, Playdate, September 1969. Photos by Max Thomson.

At the club’s weekly gathering in the Coffee Cellar, off Elliott Street, she found a collection of “young people who go along to LISTEN – not to meet people, or talk or dance. The crowd is “a montage of moustaches, denim jackets, dark glasses, sports coats, ties and suits, fur coats, waistcoats, mini skirts and moccasins …

“Henry Jackson’s local group The Killing Floor are pounding out a Paul Butterfield number. They have a full, tight sound and vocalist, Alan Hunter, in his black flopping brimmed hat, fronts the group with good, sure vocals. All six members are talented and dedicated musicians who work together well … Other musicians sit around the stage, their eyes closed, absorbing the music.”

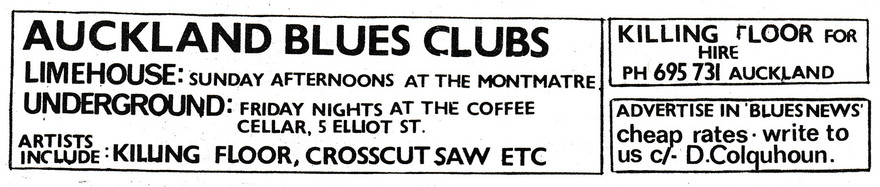

Auckland Blues Clubs listing, Blues News.

Meanwhile, the zines continued to monitor the local blues anywhere it raised its flag. In issue 4 of Blues News, Steve Hunter (a member of Auckland blues band Crosscut Saw) reviewed the blues component of the 1969 New Zealand University Arts Festival, held that year in Dunedin. He named the Windy City Strugglers as a highlight (“a tremendous jug band in the country blues tradition”) and noting that “no blues performers were allowed in the final concert” as “this was run to attract a wide variety of bourgeoisie so too much emotion or honest sexuality was out.”

Mad Dog Jug Jook and Washboard Band, at the National Folk Festival, held at the Wellington Polytechnic, October 1969. From left, Tom Crannitch, Robbie Lavën, Andrew Delahunty, Pete Kershaw, Chris Grosz.

And in Good Noise, musician John Hannan reported on the blues component of the Fifth National Folk Festival in Wellington, where “a controversy was raised when Pitt Ramsey, in his advanced guitar workshop, suggested that, before blues could be attempted a thorough technical grasp of the folk ‘finger-style’ guitar was needed…”

Blues #4. - courtesy David Colquhoun

“The blues never die,” or so the old song goes. While that may be true, by the end of the decade this particular branch of the tree had begun to wither. Leading figures such as Henry Jackson in Auckland and Bill Lake in Wellington were moving away from the more traditional forms of blues, Jackson to his Frank Zappa-inspired group Dog Breath, Lake to the eclectic Mammal.

The blues clubs were closing, and without a visible scene to document, the zines lost momentum. In the case of Good Noise, Colin Morris simply ran out of money. Poignantly, the final issue finds him auctioning his personal blues collection to pay for the magazine.

Looking back, Morris suggests that by this time “... there were so many other genres of music that people started to explore. R&B/soul music, for example, took something from the blues which really expanded my views on music as well as it did for many others.” Colin continued to work in record retail and proselytise on a wide range of music. More than 50 years on, he still does.

Colquhoun took a job as a dustman in Auckland, where he worked alongside then-aspiring blues singer and future Hello Sailor frontman, Graham Brazier. He then moved to the Coromandel Peninsula where he laboured for a couple of years as a scrub cutter. Eventually he enrolled in history at University of Auckland, becoming a tutor there. In 1990 he was appointed Curator of Manuscripts and Archives at the Alexander Turnbull Library, his dream job. It is one place where a full set of Blues News can be found. He died in 2018.

--

David Colquhoun.

Teenage blues evangelist and editor of Blues, David Colquhoun went on to become Curator of Manuscripts and Archives at the Alexander Turnbull Library. Long-distance running was another of his many passions, and he wrote an acclaimed book on Jack Lovelock, the New Zealand athlete who won the gold medal for the 1500 metres at the Berlin Olympics. A thorough obituary of Colquhoun by his friend, historian David Grant, can be read on p11 of the Archives and Records Association journal Archifacts (2018.1 edition).