In October 1990, just over a decade on from Toy Love’s final Australian performance, Chris Knox returned to Sydney for two shows. In stark contrast to their low-key arrival in March 1980, heralded by a slim paragraph in the Sydney Morning Herald Critic’s Choice column, Knox got the full feature treatment.

The 1980s were a busy decade for the Invercargill-born vocalist, composer, filmmaker, graphic artist and extrovert. Tall Dwarfs, his duo with Toy Love guitarist Alec Bathgate, had launched a lo-fi revolution in New Zealand with ‘Nothing’s Going To Happen’, their first release on new indie label Furtive Records. A reasonable pop chart hit in August 1981, it was recorded on a TEAC 4-track in Knox’s Auckland living room.

Live performances by Tall Dwarfs were few, but their run of EPs, released well into the mid-1980s on Flying Nun Records, were among the label’s most interesting and challenging.

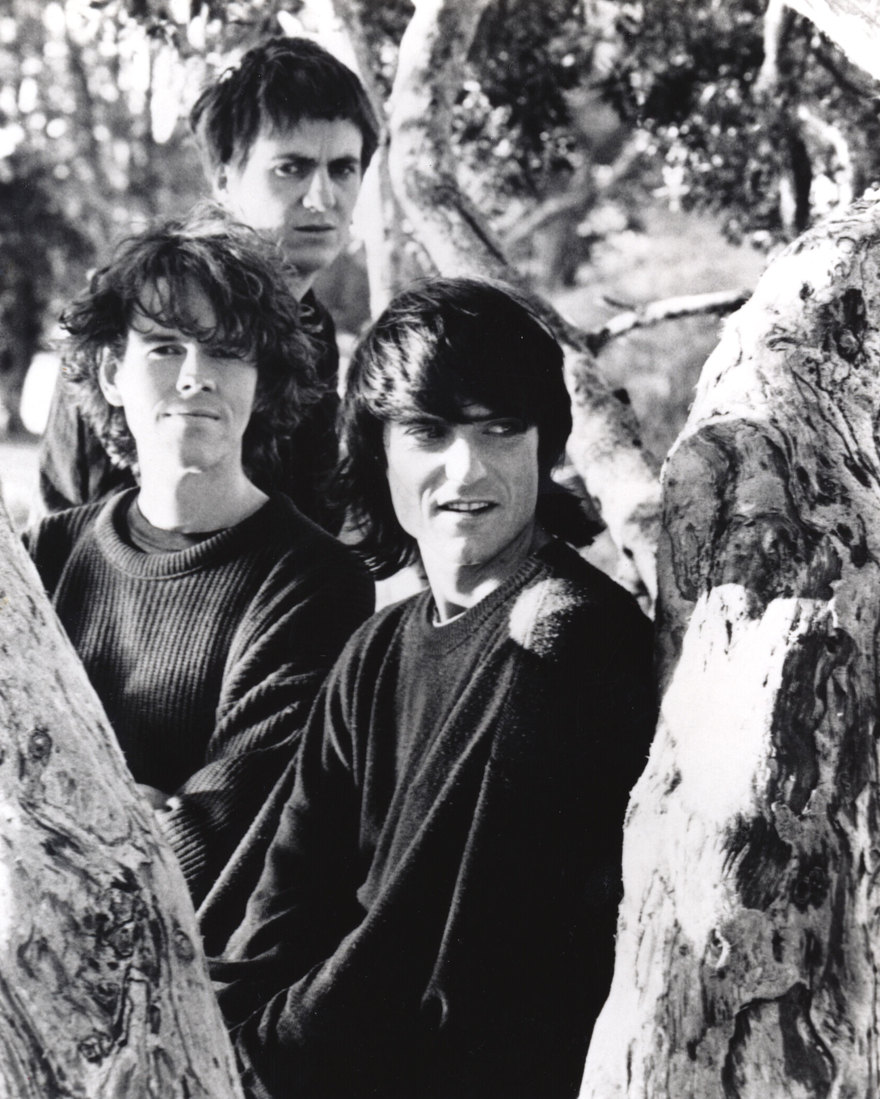

Tall Dwarfs Alec Bathgate and Chris Knox - Photo by John Ward Knox

During those years Knox found time to help raise a family, mentor younger groups, sit in on many of Flying Nun’s early productions, create art-eyed music videos, edit the brilliant cartoon anthology series Jesus On A Stick, review and illustrate records for NZ Listener, and provide weekly cartoon strip Max Media for the New Zealand Herald.

He was in Sydney to mix Tall Dwarfs’ latest album, Weeville, Knox explained to Shane Danielsen in the Sydney Morning Herald, 11 October 1990. That’s right, he was the one doing the mixing now. The outside production of Toy Love’s sole album in a Sydney studio in mid-1980 had long rankled the fiercely opinionated Knox.

That’s not all that had changed. Flying Nun, the label he helped foster, had recently signed a creative control agreement with Mushroom Records, the successful and expanding Australian independent label.

In early 1990, Mushroom Records purchased 50 percent of Flying Nun.

In early 1990, Mushroom Records purchased 50 percent of Flying Nun and together they set up Flying Nun (Australia) Ltd, based in Melbourne, to produce and promote Flying Nun Records across the Tasman. Mushroom had already tried to sign The Chills, but as the label’s roster continued to garner favourable press in important American media after late 1980s forays into Sydney and Melbourne, the label’s depth and diversity became more appealing.

“In the past, Flying Nun bands have tended to be lumped together. But there is no Flying Nun sound any more and within the label there is all sorts of music from folk rock to almost heavy metal,” Janet Dawes, head of Mushroom in New Zealand, told Dominic Roskrow in New Zealand Herald. “What’s more, there’s no reason why a lot of it shouldn’t be played on the radio. There is nothing on the Straitjacket Fits album, Hail, that couldn’t be played, for instance.”

On the back of the Australian release of his second solo album, Seizure, with its earworm single, ‘Not Given Lightly,’ and subsequent EP Song For 1990, Chris Knox was creating his widest Australian profile yet.

“New Zealand’s Chris Knox will talk quite happily about virtually anything – from comics (which he draws), to music (which he makes), to vagina envy (which he admits to feeling, sometimes). He is a perfectly rational, articulate man who is constantly mistaken for a loony,” Shane Danielsen wrote in SMH.

“The singer’s own public identity is only too clear: through his early work with Toy Love, and then with the Tall Dwarfs, he has long been seen as the eccentric father figure of the NZ independent music scene – an image that recent songs like ‘All Men Are Rapists’ and ‘The Woman Inside Of Me’ (“she’s there,” he claims) have served only to consolidate.”

The original photo used on the cover of the vinyl version of 1989's Seizure album

Meanwhile, Knox was a having high old time, gleefully dismissing New Zealand culture, “schools of art or thought” and Graeme Downes’ approach to lyric writing while big-upping individualism (it better channelled local environments), personal approaches to recording (ditto) and his next release.

“My [third] solo album, which I’m working on now, is a lot quieter, a lot gentler – except for one song, which is probably more disgustingly filthy and repugnant than just about anything I’ve ever written, I think. But that’s taken from another person’s perspective, so it’s all right. I’m all right. And I’m not mad,” Knox confessed to Danielsen, his voice “as calm, as matter-of-fact as Jack Nicholson’s.” “I’m really a very nice guy. Really,” he concluded.

Live dates at Lansdowne Hotel on 12 and 13 October followed, with Ron Peno and Brett Myers of Died Pretty in support.

It was already a busy year for Flying Nun Records-related acts in Australia. Christchurch trio Bailter Space arrived in Sydney in March 1990.

“Bailter Space is the perfect name for the latest cab off the Flying Nun rank, a three-piece band consisting of John Halvorsen, Alister Parker and Brent McLachlan, whom those with longish memories will recognise as The Gordons, noisy contemporaries of The Clean,” Jon Casimir reasoned in SMH on 23 March 1990. “Bailter Space: it’s oddly nonsensical, suggests place and movement, but can’t be dissected or analysed for meaning, in many ways reflecting the music they make.

“Music of the kind Bailter Space make is an inarticulate thing, better experienced than intellectualised – a blast to the senses which defies reaction on any but gut level. With suitable obscurantism, Parker refuses even to nominate the qualities the band strives for, other than size of sound and volume.”

“Those qualities are so important that to actually say them or try to list them is like a degenerative process,” Alister Parker told Casimir. “To say what we are trying to do doesn’t work. It’s the effect it has that matters. During last night’s performance for example, the music was carrying me into an area where I had really peculiar and interesting thought trains; quite dynamic. That is really exciting to me.

“I was hoping that for the people in the audience [at last night’s Kardomah Café show], if it wasn’t the same kind of thing, it was at least as intense as what I was feeling. I guess just to move people is something. That’s really music’s place, to give you some kind of experience that you treasure.”

"Some people might try to throw us in the rock basket, but that is like an alien world to us,” John Halvorsen added. “We are using similar tools, we are on a stage and we might look like a rock band, but it’s not how we see it. We’re just creating textures and vibrations and sounds. It really affects us harmonically. The energy is going out and we’re being affected by it as much as we are affecting it.

“One feeling I often get when playing is a feeling of weightlessness, almost elation, a feeling of travelling at great speeds. I also often feel like I’m being immersed in water, in a different time frame, so slow that everything seems to be going at blistering speed.”

Bailterspace - Brent McLachlan, John Halvorsen, Alister Parker - Photo by Jeremy Pollard

With the Mushroom deal clicking into place, delayed albums from The Bats (Law of Things) and Jean-Paul Sartre Experience (Size Of Food), plus Headless Chickens’ ‘Gaskrankinstation’ 12-inch were in Australian shops in April. The deluge of recorded New Zealand indie sounds began in earnest, with many unique items made available in Australia over the coming years.

The Verlaines returned to Australia in May 1990 and The Bats in June for shows at the Livid Festival in Brisbane and Sydney, having already fronted at the first Livid in December 1989. They returned again in August.

In the Sydney Morning Herald, Lynden Barber praised ‘Heavenly Pop Hit’ and compared Martin Phillipps to Syd Barrett.

The Chills, now signed to Slash Records in the United States and Liberation Records in Australia, arrived back in the southern continent in June 1990 on their way home to New Zealand. They had perhaps their best-realised album, Submarine Bells, under their belts, and a made-for-radio single in ‘Heavenly Pop Hit’.

The subject of two lengthy laudatory SMH articles, The Chills completed three nights at The Club in Melbourne. They had four shows lined up in and around Sydney at Tracks in Epping, Promises, Newcastle University and Paddington RSL, before heading north to Brisbane’s East League Club.

It was already clear the group were critical favourites. In the Sydney Morning Herald, Lynden Barber praised ‘Heavenly Pop Hit’ and compared Martin Phillipps to Syd Barrett. “Barrett’s songs weren’t rock at all in any traditional sense; more like nursery rhymes: elemental, charming, more than slightly crazy. It’s this unforced, singsong quality, rather than any literal influence, that makes New Zealand band The Chills so winsome; their material seesaws gently, the group seemingly lost in a haze of wistfulness,” he wrote.

Jon Casimir couldn’t resist tossing the growing Curse of The Chills myth into his appraisal of Phillipps’ group. “The band has long been known as a mobile disaster zone, and one prominent New Zealand magazine devoted 18 pages to a single article on the jinx a couple of years back.

“As sailmaker, captain and navigator of the good ship, Martin Phillipps has seen more stormy seas than he would care to remember. His 10-year career in this band has been pushed, shoved, squeezed and shunted in all directions as he has coped with 11 line-ups, the death of one member, a minor drug bust, zero financial support and a seemingly endless parade of other obstacles and harassments.”

Martin Phillipps

Tracking Phillipps to a Surry Hills living room, Casimir heard him muse on The Beach Boys’ Smile and The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s – and despair at the indifference of American commercial radio to ‘Heavenly Pop Hit’, another disappointment after all the setbacks he’d encountered.

“They call me a poet,” The Chills kingpin told Casimir with a mixture of amusement and bewilderment. “I put a lot of work into the lyrics, but I still don’t feel like I have an incredible talent for it. I use a thesaurus for rhythmical words, but I don’t believe in trying to find a more difficult word when a simple one will do. You only distance yourself from the people listening to it.

“I feel I have to be able to justify every word I use, and never waste them or contrive effect. It’s something I really despise in other people’s work. You discover, as you’re writing, the ability to have phony depth to the lyrics and you can spot that in other people’s. It would be so easy to let things go because they appear to have some sort of dark symbolism.”

Casimir hadn’t finished with The Chills, turning in a SMH review of their Paddington RSL show on 15 June. “There are times during a Chills show when you have to pick your jaw up and put it back into place. It’s not hard to work out exactly why the music made by this New Zealand band is so exhilarating, what it is that makes their angular pop sound so different – it’s just hard to work out why that difference should be so stunning,” he wrote.

“What The Chills do, purely and simply, is to invest their songs with emotion, a concept that seems awkward or stupidly self-evident on the page but, sadly, within the context of contemporary popular music, is all but revolutionary.

“The songs of Martin Phillipps are as bewildered as they are angry, as hesitant as they are confident, and as moved as they are moving. What is important to him is that they communicate that array of feelings, with all the attendant passion of each, and not just in their lyrics, but in the musical structure and sound as well.”

Those mid-1990s months saw a flood of New Zealand acts in Sydney. Jean-Paul Sartre Experience, touched down in mid-July. Ahead of performances at the Flying-Nun friendly Max’s, new spot Selinas, Lansdowne Hotel, Kardomah Cafe, Sydney University and Annandale Hotel, SMH ran the by-now expected full-length feature on the new-to-Australia group.

Jean-Paul Sartre Experience - Jim Laing, Gary Sullivan, David Mulcahy, David Yetton

Brushing the inevitable preamble on their name aside, Jim Laing told Jon Casimir, “I get paranoid with the name and title that people will think we’re too clever. The next album will hopefully have a nice simple name. We will be called The JPSE, so we hopefully won’t run up against as much interest in that side of it.”

“We wanted the title of the album to be neutral and meaningless, but not necessarily boring,” says Dave Mulcahy. “The album is such a mishmash of styles.”

Casimir was more specific in his analysis. “The music JPSE make is an intoxicating swirl of guitar, ranging through atmospheres and feelings, songs that often hit you physically before you have a chance to work out what they are about. Their material is almost invariably slow, making use of time and space in songs to explore dynamics, rather than trashing through the ubiquitous three-minute pop structure.

“Playing slow songs is our draw card and our bête noire,” Mulcahy said. “We play in a pub environment, where people go out to basically have a good time on Friday nights, but our material would work better in the concert situation, because it is quite atmospheric and slow. The dreaminess comes from living in New Zealand. It’s a dreamy place in comparison to the rest of the world.”

S.P.U.D: Lance Strickland, Glen Campbell, Matthew Heine, unknown miner, Barnaby Curnow, Peter Buckton - Photo by Alister Reid

The next Flying Nun group in town, S.P.U.D., were the nightmare to Jean-Paul Sartre Experience’s dream. Their first album, Sour, showed Flying Nun Records still had a taste for the dark and offbeat, as Melbourne and Sydney fans soon heard.

It’d be an enlightened record collector that pressed S.P.U.D. up against The Chills’ ‘Heavenly Pop Hit’ 12-inch and double 7-inch (with the unavailable in the Southern Hemisphere single ‘House With a Hundred Rooms’ included), The Bats’ ‘Smoking Her Wings’, The Verlaines’ ‘You Forget Love’ and LP Some Enchanted Evening, The Clean’s Vehicle, The Chills’ ‘Part Past Part Fiction’/ ‘Water Wolves,’ or even Tall Dwarfs’ Weeville and Chris Knox’s 12-inch of ‘Not Given Lightly’ with his wildly indulgent 1982 album Songs For Cleaning Guppies on the flipside. All were released in Australia in 1990.

Likely there were different scenes across the ditch picking up on the different New Zealand groups.

Straitjacket Fits added four more records to the list with the ‘Down In Splendour’ double 7-inch and ‘Sparkle That Shines’, ‘Bad Note For a Heart’, and second album Melt, some of which was recorded at Platinum Studios in Melbourne between July and August 1990.

Straitjacket Fits in 1990: Shayne Carter, Andrew Brough, John Collie and David Wood - Photo by Polly Borland

The Fits’ Andrew Brough fielded Shane Danielsen’s questions for a SMH article, printed on 11 November 1990, titled “Poles Apart Fit Together”. The headline referred to the increasingly difficult coupling of Brough and Shayne Carter’s songwriting styles and personalities in the talented group.

“So is it necessary, this polarity?” asked Danielsen. “Maybe it’s not essential, but I think, if it is there, it’s an incredibly valuable thing,” replied Brough. “Apart from the obvious benefits – having more songs available, and having that variety in vocals and overall sound – you find that, as a unit, the band grows between the two of you. It changes in all sorts of unexpected ways, and often takes on a whole new dimension.

“When you’re working in a pop song format, as we are, there aren’t that many things you can do: you’ve always got basically the same chord structures to play around with. There are only a finite number of progressions, after all. That’s why, ultimately, it’s the melody I’m most concerned with – there’s more room to work there.

“And, to me, if anything sets Straitjacket Fits apart, it’s that combination – the conflict of melody and noise, which we’ve got just right. Shayne’s into very rough, jagged sounds, whereas I much prefer lovely chiming guitars. They’re just completely different approaches. But between the two of us, something clicks. I don’t know exactly what it is, but it happens. It definitely happens.”

Straightjacket Fits’ first album Hail had been a disappointment to the group, but Melt ticked more boxes. It was, Danielsen believed, “an achievement far more satisfying for band and audience alike – a dense and often sublime work that saw their songwriting at its highest point since the breathtaking debut EP Life In One Chord. The group, aware that their potential was at last being realised, had settled down to the task at hand.”

In 1991 New Zealand indie groups were still on the front foot on Australia’s east coast. They’d shown strength on record and in performance, as you would expect of bands and musicians who’d been at it, in most cases, for over a decade. New Zealand had toughened them up and made them hungry, and they were more than ready for ever bigger, expectant and informed audiences and increased recording budgets.

That year, Headless Chickens broke through the pop chart and commercial radio barrier and pushed their most contemporary sounding pop song, ‘Cruise Control’ into the Australian Top 30, where it peaked at No.26.

Headless Chickens, L to R: Bevan Sweeney, Michael Lawry, Chris Matthews, Grant Fell and Fiona McDonald

New Zealand’s other best bet, The Chills, on the rebound from an American tour, staged their most wide-ranging tour yet of Australia in late January and early February 1991, taking in Melbourne, Adelaide, Canberra, Mount Druitt and Sydney, often spending multiple nights at the same venue.

There’d be “No Shortage of Kiwi Weirdos” – as Sydney Morning Herald headlined a Tall Dwarfs piece on 4 April 1991 – in Sydney and Melbourne that year. Alec Bathgate, the more retiring half of duo, did the talking this time, when he joined Chris Knox in Sydney for consecutive nights at Lansdowne Hotel on 11 and 12 April, with Knox doing two solo stints, including Annandale Hotel on the following night.

“We’re pretty much your usual, ah, semi-gifted creators.”

– Alec Bathgate, Tall Dwarfs

“I think we’re rather normal people, actually. We’re pretty much your usual, ah, semi-gifted creators,” Bathgate told Shane Danielsen with “a modest cough”.

“The difference between the Tall Dwarfs and your average band [is] bands – rock bands, pop bands – generally write songs to play live. Whereas we’ve always been conceived first and foremost as a recording outfit, so we’re operating under slightly different expectations of what a song has to be.

“The whole band format, to me, is an incredibly limiting thing, and I’m constantly surprised by how readily people accept it. And remember, this is from people who’ve been through all of that. Chris and I have been in bands [seminal NZ pop-punk outfits Toy Love and The Enemy]: we’ve done all that. But never again. That’s why the Tall Dwarfs started out as a bit of an anti-band, anti-songs, anti that whole group mentality.

“It seems to me that music hasn’t really progressed very much at all in the last two decades. I often wonder, whatever happened to people’s enthusiasm for trying different things? You look at the 1960s, at a lot of the most commercially successful stuff from then, and it was incredibly adventurous, experimental music. Nowadays you take even a minor risk and you’re like us, consigned to the independent scene for the rest of your days.”

Flying Nun Records releases in Australia in 1991 included Tall Dwarfs’ Fork Songs and a reissue of their 1986 EP Throw A Sickie, Chris Knox’s Croaker, The Bats’ Fear Of God with singles ‘Boogey Man’ and ‘The Black And The Blue’ and a reissue of their EP Made Up In Blue. Tuatara, the 1986 label compilation, got a dust down that year as well. Straitjacket Fits provided a label first when the videos for ‘Down In Splendour’ and ‘Bad Note For A Heart’ appeared on CD with the group’s current single.

The Church, an Australian group with a strong New Zealand following, came off second best in SMH reviewer Shane Danielsen’s eyes in May 1991 on a Sydney bill with Straitjacket Fits.

“There can be little doubt that New Zealand’s Straitjacket Fits are now playing at the very height of their powers,” Danielsen wrote. “Their strengths are manifold: impossibly rich vocal harmony, a perfect balance between dissonance and melody, and most of all the strong, distinctly personal, songwriting axis of Shane Carter and Andrew Brough.

“Unexpectedly, the highlights mostly belong to the latter, whose voice – in songs like ‘Down In Splendour’ and ‘Hand In Mine’ – soared above some of the most lyrical and frankly musical songs of the past five years. In all, they were little short of brilliant.”

In hindsight, 1991 was the highpoint of Flying Nun’s prolonged and delayed engagement with Australia. The seeds for what came next were sown that year. The tension between Brough and Carter saw the former leave the group. Straitjacket Fits soldiered on with the Done EP in 1992; a third album, Blow, and strong single ‘If I Were You’ were released in 1993, with a tour in March, but reviews became increasingly negative.

Chris Johnston, a New Zealander living in Australia, was frank in new monthly magazine, Juice (October 1993). Reviewing the Beyond The Jangle package tour night at Melbourne’s Punters Club that billed The Bats together with Straitjacket Fits on a six-show, seven day July tour with JPS Experience, Johnston felt the Fits were “inauspicious”. The Bats’ lack of variety in song and performance was also noted.

JPS Experience, who delivered a brilliant contemporary sounding album, Bleeding Star, with strong plucked singles ‘Ray Of Shine’ and ‘Into You,’ and toured with Inspiral Carpets in June 1993, shone that night. “Blending equal parts of monotone pioneers the Velvet Underground, the soaring guitar pop of The Church and the drowsy, drugged-chug of Spiritualised, JPS Experience was a unique experience. They, more than the others, were truly Beyond The Jangle,” Johnston wrote.

The Bats, L to R: Malcolm Grant, Kaye Woodward, Paul Kean and Robert Scott

Having toured in support of Fear Of God in October 1991 and returned to Australia in April and October 1992, The Bats continued releasing albums there. Silverbeet came out in 1993 to lukewarm reviews. “If you are a diehard Bats fan this will be a satisfying record. If you’ve never liked them, Silverbeet won’t change your minds,” Australian Rolling Stone wrote. The tide may have turned for now, but memories of The Bats would linger and they were always assured of a good reception in Sydney and Melbourne.

The Verlaines, who played shows and recorded their next album Ready To Fly at Paradise in Sydney in June 1991, jumped ship to Slash Records in a surprise announcement that year. With Graeme Downes now freed of study, they tried hard in the following years to establish themselves outside New Zealand, fully revealing their early years with the Juvenilia compilation, and launching the new Way Out Where LP with an Australian tour in May in 1993. The momentum soon dissipated.

The Verlaines, 1992. Top to bottom: Gregg Cairns, Mike Stoodley, Graeme Downes - Photo by Tony Mott

The Chills still had plenty of wind in their sails and a strong album to sell in 1992’s Soft Bomb. Slash and Flying Nun pulled two singles from the conceptually linked LP, but neither ‘The Male Monster From The Id’ or ‘Double Summer’ captured the public’s imagination, despite The Chills embarking on their longest and most wide-ranging tour of Australia in August 1992.

The Chills still had plenty of wind in their sails and a strong album to sell in 1992’s Soft Bomb.

Kicking off with two shows in Perth, followed by a night in Adelaide, The Chills hit Melbourne for six performances, including a live to air for radio station Triple J in ABC Studios on 20 August. Next they headed for Sydney, Newcastle and Brisbane.

A week earlier, SBS brodacast a TV special on The Chills, filmed with input from Martin Phillipps. Shane Danielsen, who would you had guessed by now, was a big fan, reviewed the show in SMH on 20 August 1992.

“An air of profound melancholy hung over the entire proceedings – as if Phillipps was not the major talent that he is, but rather a born loser who somehow hadn’t realised his lonely fate,” Danielsen wrote.

“We saw lots of shots of the songwriter walking down rustic Dunedin lanes, hands in the pockets of his beloved leather jacket, looking solitary and rather forlorn. Of course, he was alone: perhaps some brave soul had started out with him, but didn’t last the distance ...

“It all seemed rather unfair, particularly when the new Chills album, Soft Bomb, is such a fine, ambitious, inspiring piece of work.

“And while a friend swears black and blue that the softly spoken, unfailingly polite Phillipps is the very model of your classic passive-aggressive personality type, and so blames him for every calamity that’s befallen the band over the years, I still kinda like the guy.”

Despite the weariness evident, Phillipps still had faith in the power of his craft. “I believe that a good pop song can affect people personally, and can deal with world issues, and still be a personal and deeply felt statement from its writer,” he said. “It can be as socially conscious as the folk music of the day, and just as stirring as classical music, and just as powerful and wild as jazz. I honestly believe that.”

Having fuelled up at the Gaskrankinstation, Headless Chickens still had plenty of fuel left in the tank in late 1991. They’d been over in early December for Sydney shows at the Rose, Shamrock and Thistle Hotel in Rozelle, and the Tom Tom Club (formerly the Kardomah Cafe) in Kings Cross.

Body Blow, the Chickens’ second album, was due out in Australia in March 1992. Peter Holmes, the SMH reporter interviewing Chris Matthews, had already heard the New Zealand release. “Body Blow, save for ‘Cruise Control’, is another chaotic, hypnotic record, this time benefiting from cleaner production and more intriguing sampling,” Holmes wrote in November 1991.

“This time we went for a more overall production style, because Stunt Clown kind of fell down a bit on the fact that the songs didn’t really hold together cohesively that much,” Headless Chickens’ Chris Matthews told him. “But I’m quite happy with the way ‘Cruise Control’ fits in with the rest of the album. I think it’s an extension of what we’ve been doing. I don’t think anybody should expect us to go more towards lightweight dance music in that style, but it’s something I’d like to explore along with the harder stuff. Harder and lighter.”

Headless Chickens were back in Australia in October and December 1992. Melbourne, Canberra and Sydney shows followed in April 1993 with a Livid Festival appearance in July and further shows in October that year.

There were two more Australian hit singles for Headless Chickens, following the release of a retooled Body Blow in 1993. ‘Mr Moon’ made No.93 that year, and ‘George’ hit No.67 in 1994. But Headless Chickens were tired. The breakthrough had been made and their cultural footprint in Australia embedded, but personal problems remained.

The story of Flying Nun bands in Australia in the 1990s doesn’t end there. The 3Ds in particular would assert themselves in 1993, 1994, and in 1995, when they played all the Australian dates and the Auckland leg of the Big Day Out, as Straitjacket Fits had done in 1994. More quality recordings were made available across the Tasman, but by then the point had been made. These were New Zealand bands playing and releasing records in Australia on their terms.