EMI New Zealand HQ, 408 Hutt Road, Lower Hutt. Based there were EMI Records A&R, Sales and Marketing, EMI Music Shops, World Record Club, EMI Electronics, EMI Agency Sales for Sharp and HMV products, and all administration for royalties and copyright, the computer centre, finance and accounting. Behind and attached were the EMI manufacturing buildings for records and vinyl with an engineering and maintenance centre, and a separate building for the EMI recording and mastering studios. Two hundred-plus employees were based in the complex; adding on retail sites and branch offices, some 300 were employed at the company’s peak. - Peter Buckleigh collection

--

Peter Buckleigh, the managing director of EMI NZ in the late 1980s, recalls a decade of great change .

“So King Vinyl is dying – seems its days are numbered,” the radio host said to me over the phone from his radio station studio sometime mid 1986. He was referring to the latest RIANZ report on production in New Zealand and had called to interview me.

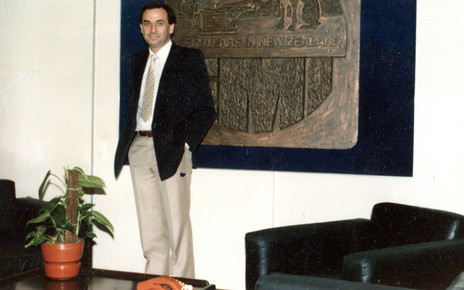

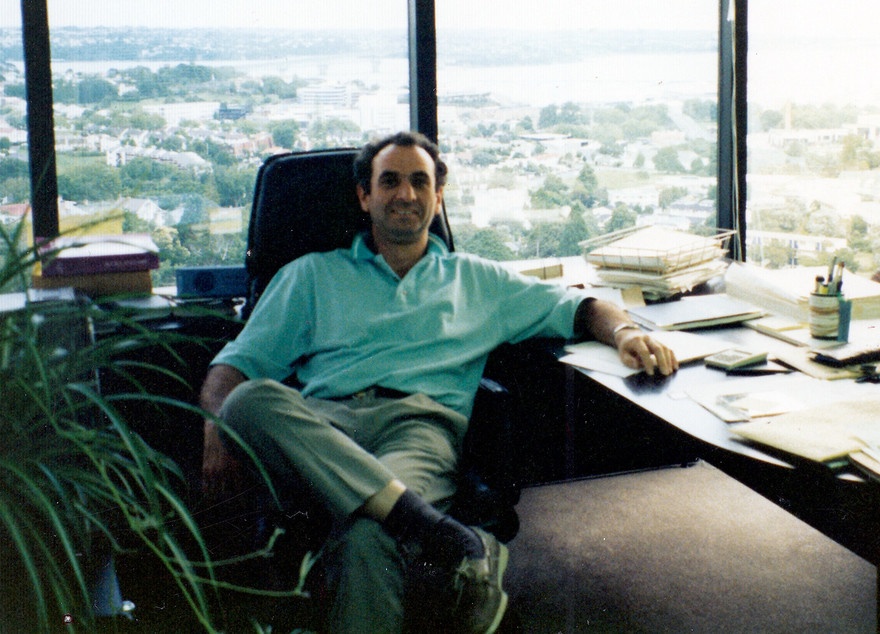

Peter Buckleigh, managing director of EMI NZ in the 1980s.

I was then managing director of EMI New Zealand Ltd, and we had the sole remaining vinyl production plant in the country. I proffered several factors behind that – the closure of the PolyGram plant and increasing imports – but the radio host seemed to prefer the headline statement and referred to it again and signed off.

At that stage EMI was servicing all the music companies in New Zealand who needed vinyl, as well as many for cassette production. But the figures I had were starting to be alarming: it was not supposed to be like that.

Peter Buckleigh at his Wellington home presenting Cliff Richard with a gold disc award. "I gave Cliff awards all over the place: UK, New Zealand, Japan …" On the right is Graham Harris. - Peter Buckleigh collection

I had started my time with EMI in 1972 at Wakefield Street, Wellington, coincidentally arriving the same day as the new MD from the UK, Leslie Hill. Initially I was sales manager, consumer goods (black & white TV, colour TV, stereos, white goods) and, following a big reorganisation which saw the company exit from most of these products, I was appointed general manager, records, in early 1974 with the label managers, sales force and distribution centre reporting to me.

EMI managers Peter Buckleigh, Leslie Hill and Barry Peace, at an EMI conference at Mt Ruapehu, 1973. - Louise Warren Collection

It was a great time, as EMI had a near-50% market share through not only its house labels EMI, HMV, Harvest, Parlophone, Columbia and others with UK, European and local repertoire, but we also had licensing deals with WEA, Motown, Decca, ABC Dunhill, Bell, Arista, and many others.

Celebrating successes by Mark Williams and Rockinghorse, 1975. From left: Midge Marsden, Mark Williams, Peter Buckleigh, Carl Evensen, unidentified. - Louise Warren collection

Fortunately, the music business was not quite new to me: my mother had run a music shop in Taupō called Harmony House. As a kid my job was to unpack the parcels and boxes delivered by the Auckland and Wellington buses and call up the people who had ordered the records to come and collect from the shop. Plus, my mother ran the local CAS (Community Arts Service) arranging for singers and musicians and painters and poets to visit Taupō and perform or teach. Many stayed in our house while there. So I knew there was a business there somewhere but never set out to make it a career.

EMI's new Record and Cassette Distribution Centre being constructed opposite the Hutt Rd HQ. Orders came by telex punched though from the various record company offices around the country or from the sales representatives on order forms and were picked, packed and distributed by the staff direct to retailers. Boxed by catalogue number, finished and sleeved records and cassettes were trundled across Hutt Rd - in a break in the traffic - for storage in the Distribution Centre.

It was a vibrant time not only musically but also as a fun business, brought to halt in 1975 when two things happened. The government slapped a 40% sales tax on records, deeming them as imports due to the copyright and royalties paid to offshore entities despite local manufacturing. And then WEA pulled out of a negotiated extended licence and decided to establish its own label, with marketing, promotion and sales company in Auckland, though leaving manufacturing and distribution with EMI NZ under revised terms.

Fred Dagg aka John Clarke signs his EMI recording contract, with producer Rick White (centre) and Peter Buckleigh. - Rick White collection

By now Leslie Hill had returned to the UK, and with WEA providing repertoire for half of the company’s full-price sales – and with the increased retail price – sales fell rapidly. The new British MD who had arrived from stints in Argentina, Pakistan and Nigeria demanded new plans to cover the shortfall. Various initiatives including TV advertising were put in place, and greater marketing and promotion of EMI and Capitol’s own repertoire saw most of the difference made up with 12 months.

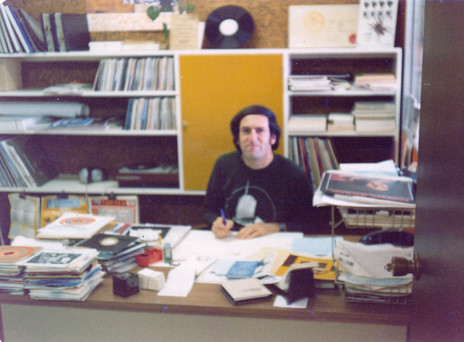

Bruce Ward, long-serving HMV and EMI hit picker with magic ears. - Peter Buckleigh collection

This led to an offer to me to transfer to London and establish a Capitol Records office within EMI Records UK. Capitol had been somewhat neglected in the UK and in 1976 I moved to London with my wife, after a period in LA. The office was a big success. I had great staff join me and Capitol hit a sweet spot; for a quarter in late 1976 Capitol was the No.1 label across the UK music business.

It was, as I remarked to a journalist, “the greatest comeback since Lazarus” given the low profile Capitol and its artists previously had in the UK.

EMI UK had stumbled badly under the Sex Pistols saga – more the fault of the EMI Ltd holding company rather than the music company – and in 1978 I was appointed general manager, EMI Pop Music, again with all the house labels reporting to me. A year or so later I became director of marketing and promotion for all music, house labels, licensed labels, classical, MOR, budget and TV-promoted records. It was a great job, with great artists, and terrific hits flowed. The UK economy fluctuated and various restructurings took place from time to time. Island Records was bailed out by EMI and licensed for a set period (EMI being far too gentlemanly to suggest Island sell out to EMI), and United Artists was merged into the EMI company. Both labels for a time were under my office in a coordination sense as they still had their own staff. The downside was a continuous churning of EMI Records UK Ltd managing directors; in the eight years I was in London there were seven of them. As well, EMI Ltd fell on hard times as various parts of the business empire suffered, and by the early 80s Thorn and EMI had merged to create a new company which, of course, needed to learn all the businesses.

Rihai Poipoi and Kit Kingston in EMI record sales, Lower Hutt, 1970s. - Peter Buckleigh collection

In 1983 I suggested I move on, as another MD was due to arrive and I wanted to be closer to my aging parents in New Zealand. This resulted in me being appointed resident director in Japan for EMI Music International and representative director of the joint venture operating company Toshiba EMI Ltd. It coincided with the development and growth of the CD and while, ostensibly, I had been seconded to give some marketing impetus to international repertoire there, it rapidly became apparent that the burgeoning CD business had to be the focus of much attention. EMI (and Thorn) had missed out on the early development and, by the time they realised, they had to catch up: only Toshiba EMI (TOEMI) was able to manufacture the discs anywhere in the EMI empire. Philips and Sony, the developers of the CD technology, declined to assist EMI – and TOEMI had been hamstrung by EMI vetoes on capital expenditure, so had limited capacity.

I quickly learnt the technology and the job became one of convincing Thorn EMI to loosen the purse strings. And then to ramp up capacity with the assistance of Toshiba and coordinating production of CDs in Japan for EMI Worldwide, as well as coping with the demand in Japan. Vinyl manufacturing was progressively stripped out of the Gotemba factory as high-tech clean-room facilities were built to house the CD presses. Additionally there was the negotiating of the building of “turnkey” (all-in-one) factories in Japan through TOEMI and Toshiba subsidiaries, for delivery to Capitol in the USA and for EMI in the UK. All alongside the creative aspects of the music and artists in Japan, or being released and visiting the country.

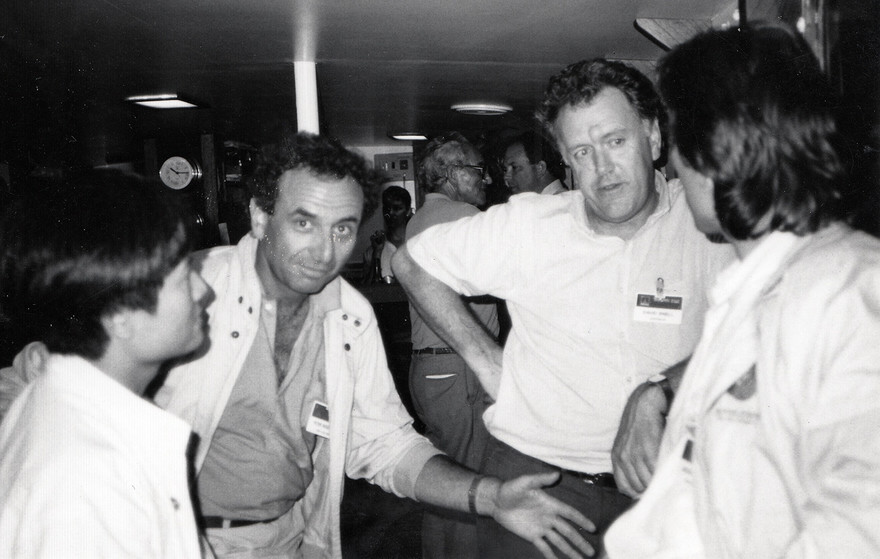

"Myself, former EMI NZ managing director David Snell and, on the right, former New Zealand sales Manager Lachie Rutherford (by then MD of EMI SE Asia) . Many employees - Peter Dawkins, Alan Galbraith, Peter Mathews, Andy Yavacis, Paul Smith, Robbi Walker, Andy Clark, Noel Muller come to mind, and others - moved or were transferred overseas. The company was like a university for the music business." - Peter Buckleigh collection

Sometime in late 85 there was a reshuffle of jobs in various parts of the world and I was asked if I wanted to return to New Zealand. David Snell, the current managing director of EMI NZ, was wanted in Europe as manufacturing director; someone new was heading to Australia; there were changes in South America; and EMI America was having great success. So out of it all I thought it would be an opportunity for our family – there were now two children – to be with close family in New Zealand and to be near my parents as they got older.

Former EMI NZ managing director David Snell and his wife Rosemary headed off to Europe from New Zealand for a position as MD of European manufacturing. On arriving in Los Angeles he was asked to instead become MD of EMI Australia. - Peter Buckleigh collection

I met up with David Snell at the EMI NZ head office in Lower Hutt late November 1985 and he outlined the initiatives taking place with the business:

PolyGram was closing its record and cassette manufacturing facility and shifting all to EMI, so EMI was the prime supplier for the country.

The distribution arm of the company had, in addition to the house labels, CBS, RCA and Virgin. (I think WEA and PolyGram had their own in Auckland.)

The EMI Music chain of shops was being expanded to 25 with the purchase of shops in Christchurch and the owner of those becoming retail chief.

EMI Records itself in New Zealand was having a stellar run with Talking Heads, David Bowie, Diana Ross, and others in the charts.

A new computer programme was being developed by EMI NZ with a specialist IT company to enable all the music companies to link with the factory and distribution arm to place orders for manufacturing and distribution to shops.

The World Record Club had record membership.

Demand was starting for CDs.

Plus, the New Zealand Government was abolishing sales tax and duty and replacing them with GST, so retail prices would fall.

Import controls were still in place for many products, including music, and available licences would be used to bring in CDs.

On the face of it EMI NZ had nearly 100% of production, 50% of distribution and, through the shops, sold about 20-25% of all at retail.

Too good to be true really.

The only business arm seemingly having trouble was the recording studio. Its location in Lower Hutt was proving to be a turn-off for commercial customers and local recordings were not being made (this was prior to the days of radio stations having a New Zealand music focus). However [producer] Peter Dawkins told me before I arrived that he wanted to relocate back from Australia, where he had been a go-to producer, and an arrangement was made to lease the premises to him and he would take over the business. This seemed a solution.

1990s: "Outside EMI Music Worldwide HQ, Gloucester Place, London, with Neil Finn, my wife Lesley and son Mike to the left." - Peter Buckleigh collection

I told everybody that CDs were booming in Japan and elsewhere. However, while vinyl production fell off rapidly in Japan, the same was not happening elsewhere – or not yet. David Snell mentioned that RIANZ had approached the Minister of Customs [Margaret Shields] to discuss having flexible import licensing to bring in CDs, as there was no New Zealand manufacturer; they expected to have that meeting during December.

I returned to Japan to hand over to the new person and, as a family, we moved back over Christmas and New Year. I moved into the job early January, working with David for a few days before he left. As it turned out he only got as far as Los Angeles before being told to turn around and head to Sydney. The appointee there had quit on day one for another job and David was asked to take over as MD of Australia.

Peace and love, Japan, 1995: an award to Ringo, on tour with his All Starr Band. With Toshiba EMI President Masaaki Saito. - Peter Buckleigh collection

That same day the Minister of Customs announced that not only CDs but all music was freed from import licensing. This was totally unexpected. The initial reaction broadly from RIANZ members was that coordinating orders from offshore – particularly Australia – would be too great a task and most probably, given the size of the market, New Zealand orders would be filled behind those for the parent company. It would also be difficult for the independent labels to get any kind of proper service. I was not so sure about that as, by the time I had left Japan, exporting CDs was quite seamless given the deadlines and I had noted that large import stores were opening all over Japan accessing new releases, making them available within days of a US or UK release.

I encouraged the factory management to attend to all customers as best they could, given priority demands in response to airplay and marketing. In return I was told the new computer programme, due to become active over Easter 1986, would greatly streamline activities.

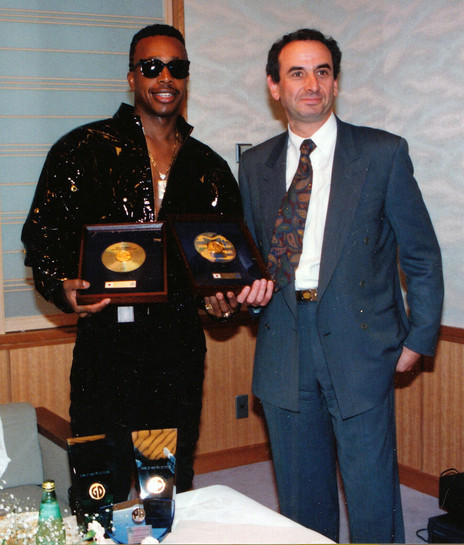

Peter Buckleigh with MC Hammer in Japan, 1990s. - Peter Buckleigh collection

Just before then, the chairman of Thorn EMI visited and, after the usual presentation of the company’s activities, he outlined plans for a ramp-up worldwide of the HMV retail shop chain as a separate business. He thought New Zealand might well be part of the structure. HMV shops were a big business – by comparison the EMI shops in New Zealand were miniscule – but he said that the new management of HMV would assess whether to incorporate. It was a little known fact that EMI NZ had more shops than any other country in which Thorn EMI had a business (except the UK) and I remarked it would be hard for them to leave them out.

EMI NZ, 1980s: a hug from Marie Fredrikkson of Roxette in Auckland. Per Gessle of Roxette is second from left, EMI NZ finance chief Andy Clark is to the right, and EMI promotion manager Dianne Moffat is in the orange jacket. - Peter Buckleigh collection

During Easter the new, integrated, manufacturing and distribution computer system was switched over, with deadly consequences. Some flaw saw all the data for all the companies disappear into a black hole. Despite 24-hour days over Easter, by the Tuesday there was no solution other than to revert to manual systems while all was reloaded. In particular, production stalled, releases were delayed, stock replenishment orders backed up and phone lines tied up for hours as all attempted to placate customers and provide a service that was proving less-than-desirable compared to prior working experience.

A timeline was set with the computer bureau to get a fix but as this dragged on, the bigger companies started to pull in vinyl from Australia and by the time the fix was implemented and proven reliable – several weeks later – fears of a poor importing service had been eliminated. Where we had masters, companies continued to order through us but it became apparent that new releases were being imported direct and by the year end production numbers were nowhere near the original projections at the time of the PolyGram closure. Plus, CDs were growing in popularity and the World Record Club, hitherto a reliable monthly production customer, saw a drop off in demand for vinyl, with members increasingly requesting CDs. Sourcing CDs for them was very difficult as their releases did not follow what EMI and others were manufacturing in their factories globally. Overall sales declined quite quickly despite efforts to provide alternative non-music products to members (easily procured with import controls having been dropped across a whole range of consumer goods).

By mid-1987 the factory was producing alarming losses despite cutbacks in overheads and costs. Thorn EMI NZ advised me that HMV stores would be established in New Zealand and asked for meetings on how to slice the very profitable retail business out of EMI NZ. The arrangement with Peter Dawkins to operate the recording studio did not work out and he returned to Australia, so that was back in our hands. Also, CBS/Sony told me that they would cease having any more vinyl made by us and others started indicating the same.

The worldwide EMI finance director was a colleague from my London days now based in Los Angeles, and at my request he came to see me. Together we looked at all the numbers and could see that the add up was for ongoing issues. He returned to LA and set up a review with the EMI Music chairman and CEO, a former head of Capitol Records whom I knew well. I went to LA to talk him and his staff through all the issues. Placed over the top of growth numbers for CD and declining vinyl production worldwide, there was no ready solution for the company structured as it was – and as retail was about to be hived off, a much smaller operation would have to be established.

Cliff Richard being presented with a gold disc, at a party held at Peter Buckleigh's home in Wellington. Back row, from left: Bruce Ward, Kieron Green, Rosie as we called him, Cliff Richard, Jenny Voss, Buckleigh's personal assistant Joan, Steve Leifi, and Graham Harris. Front, from left: unidentified, Peter Buckleigh, Dianne Moffat.

The existing structure of the business had been set up behind comprehensive import controls which were no longer in existence. The advance in technology with CDs, and with video becoming a big component as well with VHS, Betamax, and laser discs – along with the ready availability of product production for EMI’s house labels and artists from Australia and elsewhere – all called for a comprehensive revamp.

I said to them that, given the circumstances – and also that the New Zealand economy was going through wholesale changes from rigid government control to a completely open market – it would be best to advise the staff in Lower Hutt that there was no longer the ability to keep production based there in the country, and that there would be large-scale redundancies. This was agreed and I returned to New Zealand to formulate plans for an EMI NZ operation which would be on a smaller scale, based in Auckland, incorporating an EMI Music marketing, promotion, sales and finance/admin office, and a shared distribution facility with some of the other companies.

Before advising the staff I met with local Labour MP John Terris. He had been a regular visitor to the company and often addressed the staff in the cafeteria. He was shocked when I told him what was to happen and arranged a meeting for me at Parliament with various senior government ministers. The responses generally were along the lines of some business activities were likely to be affected with the changes introduced. I said I felt that the Hutt Valley would be hollowed out as more companies adapted to an open market and no longer had the need to base all operations in the country.

I advised all the staff that we would be closing vinyl production by a certain date followed by the studio, cassette production and distribution centre ceasing later, and that this would lead to a relocation of selected activities to Auckland. Eleven unions were involved in the redundancy talks and a timetable and payments agreed. This took place over several months. The retail business moved out first and, through Thorn EMI, we found a location for an Auckland office and separately a distribution centre.

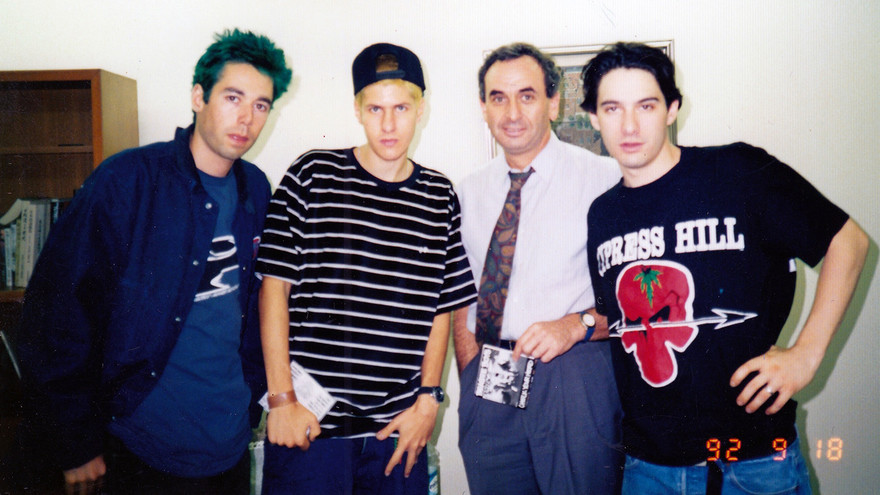

Peter Buckleigh with the Beastie Boys, September 1992. - Peter Buckleigh collection

David Snell was still a strong supporter of vinyl and cassette production in Australia and, as he knew the equipment well, asked for all but four presses to be shipped to Homebush, EMI’s manufacturing plant in Sydney. The four not wanted were older models, less efficient and needed continuous maintenance. Through Tim Murdoch at WEA NZ an introduction was made to some people in Hamilton and they expressed an interest in taking them over. They visited us several times in Lower Hutt and I had the staff take them through the whole process so that they understood what they were getting into. I seem to recall they were associated with Tainui and saw it as a way to help their people and culture. In the end they backed away and they were dismantled and sold for scrap.

The World Record Club was put up for sale and some investors from Australia bought it off us. I had previously offered it to Bertlesman as they had similar operations around the world, but they declined – only to purchase it later, I heard from the investors.

Once the building was stripped of the plant and sent to Australia (some studio equipment remained in New Zealand, sold privately) it was put up for auction but there were no takers. About a year later, following a revaluation after the financial meltdown in New Zealand, we received an offer from one of the Riddiford Investments businesses and they purchased it off Thorn EMI. The distribution centre building across the road was sold to a former employee who had established a very successful business importing video players, a brand that we had to drop as Thorn EMI had the rights to SHARP and as such they clashed.

Peter Buckleigh in EMI NZ's office in Ponsonby, c. 1988, after the company's relocation to Auckland. - Peter Buckleigh collection

There was some criticism of the company abandoning production in New Zealand but, on talking to me, most commentators understood the background.

Some did not. Peter Sinclair accused me on radio in an interview of killing off the local music industry. “Plug pulled, vinyl gone, studio shuttered, Kiwi music abandoned,” he said, even though I outlined how Stebbing’s, Marmalade and others still existed and production in Australia was utilised by all the New Zealand record companies now. All good fun and part of the cut and thrust of an emotional business.

Others loved to stir things up. “A second-rate music company with a third-rate factory run by a fourth-rate people,” one local music company chief was quoted as saying in an article.

Revenge was sweet when I hired his long-time PA/secretary and shifted the Auckland office of EMI into the same building but on the top floor. Only three staff, plus myself, moved up from Lower Hutt to establish the new business operation. Fortunately, the existing Auckland office had some excellent people and with a few more hires it became very successful in the following years.

In January 1990 I returned to Toshiba EMI Japan where I spent all of the next decade. At one stage in the mid to late 90s it was by sales value the biggest company in the EMI empire but that’s a whole other story ...

Japan, 1995: Peter Buckleigh presents an award to Ringo Starr, for the Beatles Live at the BBC album. He was on tour with his All Starr Band. With Toshiba EMI President Masaaki Saito. - Peter Buckleigh collection

Japan, 1992: a presentation to George Martin and his wife Judy, with Toshiba EMI President Masaaki Saito and others. George Martin came to Tokyo to help with the promotion of the Red and Blue Beatles albums, released for the first time on CD. "Earlier that day I introduced him to the vast gathering of Japanese media; he was revered there as a god." - Peter Buckleigh collection