A moment from a 1996 ENZSO gig at the Aotea Centre, Auckland: Dave Dobbyn, Neil Finn, Annie Crummer, Tim Finn, and the NZSO cellists.

Auckland, March 1996 – Being able to play music by ear is a limited skill, Benjamin Britten once said. But he never met Eddie Rayner. As the long-serving keyboardist with Split Enz, Rayner didn’t just tickle the ivories, he “radiated the 88s”. That’s the number of keys on a standard piano, and Rayner made sure he used them all.

While the Finns and Phil Judd got the kudos for writing the songs, it was Rayner who was the musical linchpin of the Enz’s theatrical dynamics. His baroque style was both eclectic and eccentric; between bar lines he could change course from a Rachmaninoff arpeggio to a Jerry Lee Lewis glissando, quoting a TV theme or a slice of Kiwiana kitsch along the way.

Benjamin Britten would be surprised by what those who play by ear can now achieve when talent is combined with technology. Still unable to read a note of music, Rayner has arranged a selection of Split Enz classics for full symphony orchestra. They have been recorded by the NZSO, and can be heard in concert this week performed by the orchestra with guest vocalists Tim and Neil Finn, Dave Dobbyn, Annie Crummer and Sam Hunt, plus the National Youth Choir. Rayner will once more be at the keyboard – and no Enz concert would be complete without a solo from Noel Crombie on spoons.

Rayner only ever had four piano lessons as a child. Ironically, he says that classical musicians regard him with envy, that he isn’t “fettered” by his training. But he has always found the idea of working with an orchestra intimidating. “I could probably have done this years ago, but I’ve been insecure about the whole orchestra thing because of my lack of classical and theoretical knowledge. Whenever anyone mentioned the word orchestra, I tended to run away. Now I feel totally confident.”

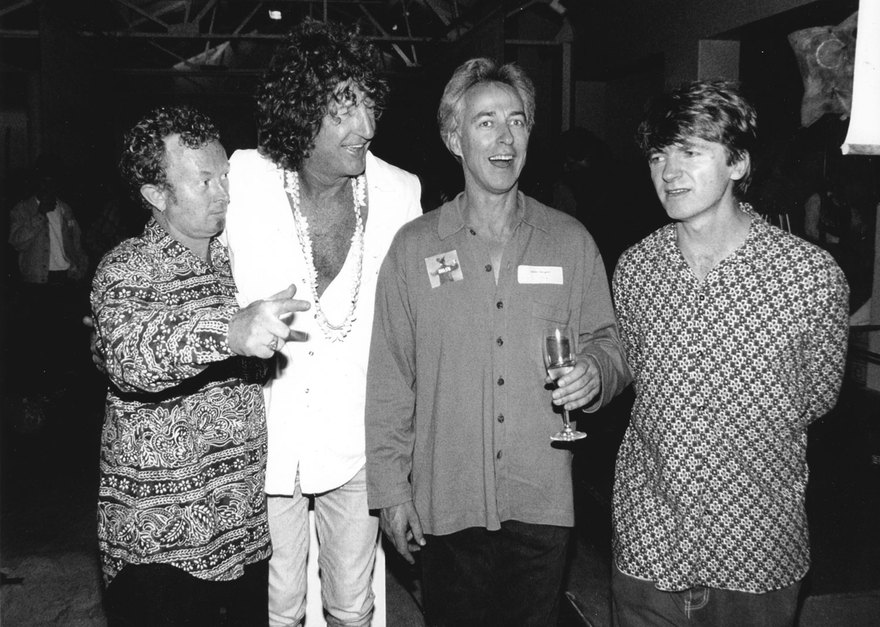

Backstage at a 1996 ENZSO gig in Auckland: Dave Dobbyn, Sam Hunt, Eddie Rayner and Neil Finn. - Photo by Murray Cammick

He didn’t feel that way when he first began the project, over a year ago. “I was bluffing my way around town talking to arrangers and composers because I had absolutely no pretensions that I could arrange it. But I wasn’t entirely happy, I had a gut feeling that I should just do it myself.”

Rayner relates his technique with ingenuous candour. After going to concerts in Auckland “to get a rough understanding of what is actually in the orchestra”, he wrote the arrangements on his keyboard at home, which is linked to an old Atari computer. “I’d do a rhythm track first with a piano, then colour it in with the orchestra. I’d dial up my strings, flutes, trombones – that’s when I started to learn about the ranges of the various instruments, what they could do. I was under some wrong impressions.”

With his ideas down, Rayner made many visits to Auckland transcriber David Woodcock, who transferred the arrangements from disc to manuscript, and smoothed out a few orchestral misconceptions. “Sometimes correctly, sometimes not,” says Rayner. “He taught me so much. He’d say, ‘They’re going to hate you for playing this’. Though in some cases he was overly cautious or sympathetic. I wrote some reasonably difficult stuff for the orchestra. I didn’t want the project to bland out, to sound like muzak. That was one reason I kept them as songs. As soon as you get strings playing a melody which is normally sung, you’re in danger of sounding like beautiful music.”

With its genre-breaking diversity, the music of Split Enz is far more suited to orchestration than other recent victims, such as the Rolling Stones and Pink Floyd. Hearing the London Philharmonic trying to find things to do in an instrumental version of ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash’ is an embarrassment to all. “I was probably advantaged by the fact that a lot of our stuff is highly arranged in the first place,” says Rayner. “There was plenty to work with.”

ENZSO tour programme, New Zealand, 1996

The “excessive, naive” arrangements of the early Enz songs seemed anything but when written for a full orchestra. “I was very conscious of doing too much, making it too big, too ‘overblown’, as Neil would say. My response was, well it is the symphony orchestra, there are 100 people playing, plus a 40-piece choir – it is going to sound big.”

The results are indeed big, with Ben-Hur fanfares and Lawrence of Arabia panoramas. For, more than anything, the orchestrations are reminiscent of the golden age of movie scores, before the bland professionals took over: when technique mixed with irreverence and some epic bombast made even the triangle player feel wanted. Just as Rayner has always done on the piano, he uses every colour on the musical palette. But the orchestral versions also confirm the strength of songs which, as Rayner admits, “were often badly served on record” or are now taken for granted in the graveyard of classic hits radio.”

Neil Finn sees the project as “a very Split Enz kind of thing, the crossing of another boundary. Particularly in the early days, Split Enz almost perversely refused to be categorised. We’d take on a little burlesque, a little classical, anything that seemed to fit. So it makes perfect sense the orchestra should be playing them.”

Gaining the acceptance of his former Enz colleagues was the most important thing for Rayner. Although they encouraged him throughout, he could sense a wariness about how it would work out. “Everyone was a little on the offensive until it was recorded.”

Neil and Tim Finn confirm those initial mixed feelings: “It had a risk of being, at worst, pompous and pretentious,” says Neil.

“So it was fraught. But Eddie’s commitment to it – and his arrangements – were what sold me. When I heard the demos I thought, this is pretty classy stuff. In a way he was the orchestra in Split Enz, so it makes good sense that he takes on the orchestra proper.”

“We were a bit afraid, but he’s done a great job,” says Tim. “I love the fact that Sam Hunt is doing ‘Under the Wheel’, that’s really magical to me. And Dave does a brilliant ‘Poor Boy’.

“I like it – it validates the music. When someone else sings one of your songs you think, oh, it must be a real song. Because you’re never quite sure.”

Rayner found immediate support, however, from the management of the NZSO itself. “They were very keen on the idea, particularly the general manager Mark Keyworth. He was genuinely interested, but I think it was also a way of killing a few birds with the one stone. They’ve been copping a lot of flak recently about not supporting New Zealand music.”

ENZSO - album advertisement, New Zealand

Rayner didn’t get to meet the orchestra until the day of the initial read-through, which seemed more like an audition for his scores: “After all, they can’t have any old riff-raff coming in and employing the orchestra,” says Rayner with a laugh.

He did get a rude shock though: the orchestra’s sense of time was totally different to his own. “I came home thinking, these guys can’t play in time. But it’s their own sense of time, the conductor is totally pivotal. A lot of the problems relate to the sheer size of the orchestra. From what I hear on the tapes, the percussionists at the back play way ahead of the beat so their sound reaches the audience at the same time as the other sections. They can’t really hear each other.”

One cliché Rayner was pleased to dispel however, was that our biggest band couldn’t swing (just in case, he altered ‘Strait Ole Line’ to a four-square rhythm). “Things are changing,” he says. “A lot of the band are Americans, so it’s evolving. But it’s quite strange, there are factions within the orchestra. Remember being in a classroom, where the swots would sit up the front, and all the bullies down the back? That’s what the orchestra is like.”

Neil Finn sees Rayner’s arrangements as a resource to be used in schools, “to break that problem of not having much New Zealand music around.” It’s likely that the album could become a New Zealand version of Britten’s Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, a Tiki Tour through the instruments to stimulate generations of bored music-option truants. In one fell swoop, the project helps solve local music content dilemmas for both the NZSO’s summer pops season and National Radio. It’s also a celebration of Split Enz, says Tim Finn proudly. “And why not?” he says. “We haven’t overdone it, flogged a dead horse. We’ve done one reunion tour which was a huge celebration and enabled a lot of young kids to see us for the first time. And that will never happen again, almost certainly. So why not do this for the cheese-and-claret set? No – hopefully it’ll spread a bit wider than that!”

Enzso: the Encore

Auckland, October 1998 – When New Zealand’s two biggest bands got together in 1996, it was a celebration that took everyone by surprise. Enzso, the album of Split Enz songs arranged by Eddie Rayner and performed by the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, with members of the original band and other special guests, captivated the public on both sides of the Tasman.

Over 45,000 New Zealanders bought the album (that’s three times platinum) and just about as many attended the Enzso concerts. In Australia, the figure was 200,000: Enzso was the fifth biggest-selling album of all albums released there that year.

“I wasn’t surprised that it was a success, but I was shocked by the level of that success,” says Rayner, with typical candour. “One of the facts of life is profile: if you’ve got famous people on board, then they will attract attention. With the calibre of singers on Enzso, the odds were high of it succeeding.

For Enzso II, released this month by Sony Music, Rayner’s orchestrations are once again brought to life by conductor Peter Scholes. “We talked a lot about what we wanted to achieve,” says Rayner. “For me, the aims were simple: to air another batch of deserving Enz songs. I was smitten by the whole orchestra thing, by the feel of playing inside that sound: that warm, luch, incredibly wide dynamic. It was a new area for me, and that first album initiated that curiosity for me. That intensified once I went on the road with the NZSO.”

Rayner is the first to admit that with Enzso he was “a novice”. This time, with one album of rich orchestrations successfully completed, he was a lot more confident. “I’d learnt a lot, particularly from Dave Woodcock, who transcribed my arrangements. I learnt things like how to beef up the bottom end, that the timpani aren’t actually drums at all. I thought they were a drum kit! But they’re more like a percussion punctuation machine.

“I’m still wet behind the ears when it comes to most of the instruments. But I’ve leant about their ranges, and combinations of instruments that work well together. I’m a bit more sussed. I particularly love the woodwinds, they can be very quirky. I guess that comes from the whole Split Enz thing. They’re very flexible. I’m still not sure about the brass, how fast you can push them to play before they decide to walk out!”

ENZSO poster, Australia, 1996. - Koji Kumada, Kia Kaha

Rayner sees another step forward in the way they recorded Enzso II. The sessions used techniques of recording rock music, to gell the singers and the orchestra together more. “I wanted to make the orchestra more of a groove band than a note band, to get the feel of the songs. They were written as humble pop songs, that’s what Neil Finn said right from the start. I think part of the humble song is the feel that’s created.”

So all 90 members of the orchestra donned headphones to tighten up the rhythms. “Orchestras are so big, compared to rock bands, they come and go. I knew there would still be a little bit of breathing about the beat, a lag between sections. This way, the singers could fit in better with the ‘rounded’ beat of the orchestra.”

The singers who appear on Enzso II are Dame Kiri Te Kanawa, Margaret Urlich, Jon Stevens and, returning from Enzso, Dave Dobbyn. The Finn brothers don’t appear on the album, as both are ensconsed in the solo careers. Neil Finn is currently touring Europe promoting Try Whistling This, and Tim is finishing off his next solo album.

“They’ve got their own careers,” says Rayner, “this is what I’m doing. I’m still challenged by what I can do with these songs and the orchestra.

“I want the character of the songs to come through, and also the character of Split Enz.”

“I want the character of the songs to come through, and also the character of Split Enz. I love working in this idiom. In a way it’s daunting that the first projects I’m doing in the orchestral idiom are so high profile. It’s a weird situation to be in.”

What was it like working with Dame Kiri? “One of the secrets about dealing with people is to treat everyone the same,” says Rayner. “Then your attitude makes people feel comfortable right from the start. We recorded ‘Bon Voyage’ in London. She said, ‘Yes, I’ll do it, but I want to start at 10 o’clock in the morning and finish by 12’. I thought, no one does a vocal in two hours. But she was in and out in an hour-and-a-half. Talk about professional. She came in, had it completely sussed, put down a few versions and went home. A very easy experience for both of us.”

With Enzso II completed, Rayner is back at work as an independent producer based in Auckland. Recent projects have included albums with The Exponents, Dead Flowers and, just completed in Australia, an album of classic New Zealand songs performed by Margaret Urlich. Rock music is still in the blood of the eclectic keyboard whiz. “I still love performing live,” says Rayner. “I love grungy guitar, drum kits, the volume thing. But I now love the orchestra. The only thing I haven’t done so far is a jazz album.

“Maybe,” he says with a laugh, “I should record Crowded House songs, done in bebop style!”

--

First published in 1996 and 1998.