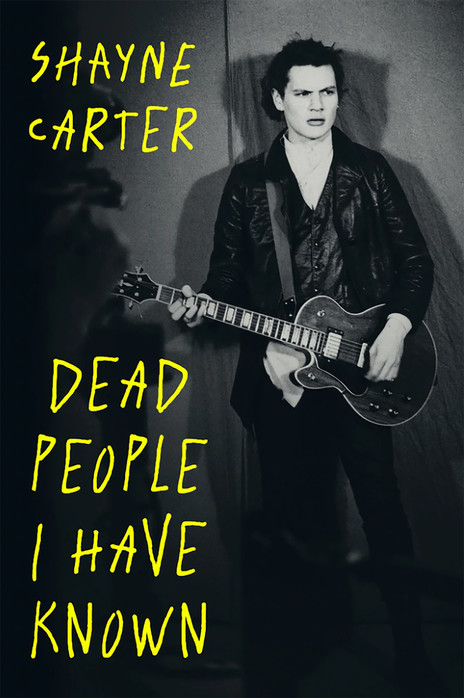

By sweeping the general non-fiction categories at the 2020 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards, Shayne Carter has not only won yet more recognition for his riveting autobiography, Dead People I Have Known, he has also capped a vibrant period for local music memoirs.

The book, which traced Carter’s life and music career through Bored Games, The DoubleHappys, Straitjacket Fits and Dimmer, won him the $10,000 general non-fiction award. Shortlisted against works about the life of lawyer-activist Shirley Smith, a history of New Zealand women’s poetry and a memoir inspired by the Erebus tragedy, it also won him the $2500 prize for best first book in the category.

Dead People I Have Known, by Shayne Carter (Victoria University Press, 2019).

In his acceptance speech via a Zoom livestream, Carter said, “If there’s one thing I learned out of this experience it’s that writing is pretty hard and it takes a lot of application. And with a ten-percent royalty rate I know people aren’t doing it for the money.”

Publishing around the world has, in recent years, been in thrall to the age of the creative non-fiction and the gritty memoir. With its contemplation of Carter’s 1970s Dunedin childhood, and his volatile family and personal life, Dead People I Have Known transcends being another indie-rock memoir just for old fans. Its publication by literary powerhouse Victoria University Press said as much.

The Ockham judges agreed: “From the first page, Shayne Carter invites the reader to jump right in and come along for the ride. What follows is an illuminating insight into his childhood, shaped by violence and addiction, of a boy who didn’t fit in and felt saved by music … it is a fascinating look at what it means and feels like to be a creative obsessive – pushing towards perfection despite, and because of, addiction, oblivion, and isolation.”

When, in 2015, Andrew Schmidt wrote the AudioCulture article “Faith Singers”, covering books about New Zealand popular music from 1964 to 2015, his survey was long on weighty works of history and best-of volumes. It included such definitive histories as Stranded in Paradise by John Dix, and Blue Smoke by Chris Bourke; in 2017 Bourke delivered Good-Bye Maoriland: The Songs and Sounds of New Zealand’s Great War, a prequel to his earlier award-winner.

Notably, Schmidt ended his list with Gutter Black, the 2014 posthumously-released autobiography of Dave McArtney, a book that he noted was “perhaps New Zealand’s best-realised music book.”

The Hello Sailor guitarist’s reflections seems to have started a wave of local musician memoirs to readers primed for New Zealand pop history tales by such things as this very website, the NZ Music Awards’ Legacy prize, the Taite Prize Classic Album, and a raft of feature documentaries such as the recent films about The Chills and Head Like A Hole.

As his book shows, Carter’s dramas would be a challenge to capture in any screen adaptation – and you might come away with mixed feelings about the leading man. But it’s a terrific read, and, like McArtney’s, one of New Zealand’s best-realised music books, ever.

Still, it has had some solid competition in recent years …

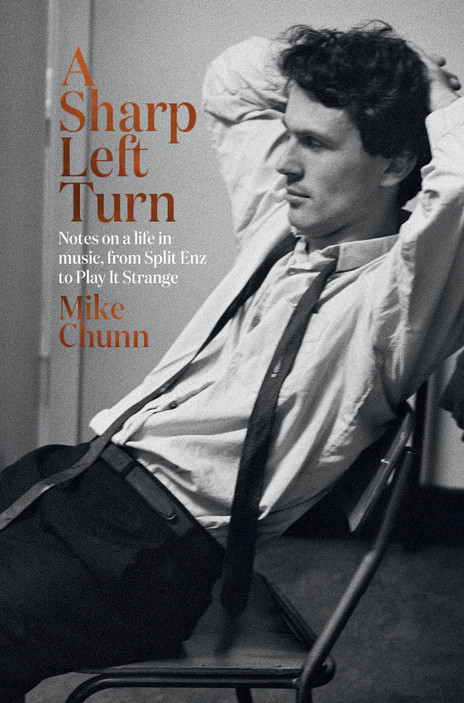

A Sharp Left Turn, by Mike Chunn (Allen & Unwin, 2019)

Mike Chunn gets mentioned a couple of times in Carter’s memoir, mostly as part of a young Dunedin punk's disdain for both musicians of an older generation and record company guys from Auckland. Chunn was both. He doesn’t return the compliment in his 2019 memoir A Sharp Left Turn.

Having already penned a book about his first band Split Enz and published a few other things, A Sharp Left Turn is not Chunn’s first time in print. While 1992’s Stranger Than Fiction: The Life and Times of Split Enz made the band itself the leading character, his adventures as a member of the original line-up make up only a quarter of the 380 pages in his latest book.

He also explores his childhood, his wide-ranging career throughout the years behind the bass, then behind various New Zealand music-industry desks, which made him – in the early 80s – possibly New Zealand music’s most important A&R man. There’s also contemplation of the mental health battle with agoraphobia which made him decide to quit the Enz in 1977, then enjoy later domestic rock stardom in Citizen Band alongside brother Geoff.

The closing chapters might be devoted to his good works as the head of APRA and the Play It Strange Trust, but Chunn’s evident passion for the work of the young songwriters which his latter organisation mentors gives the writing an emotional kick in its closing overs.

Sportsman of the Year, by Jan Hellriegel (Seahorse Swim, 2019).

Also mentioned in Carter’s book – in passing and discretely unnamed as his girlfriend at the time “who was on a major label” – is Jan Hellriegel, who in 2019 delivered her own memoir which formed part of her self-released book-album project Sportsman of the Year.

By itself, the book itself is a rarity and a possible first: a local woman artist writing about her career. But tied to the album, with each chapter of her non-chronological memoir loosely tied to a song, it was also an ambitious marriage of past and present, and a celebration of her life now. After the demise of her Warners solo deal, which produced two albums, It’s My Sin (1992) and Tremble (1995), Hellriegel eventually established a career in music publishing with occasional forays back to the studio which produced the 2009 album All Grown Up.

Ten years later, her engaging book, subtitled “A Suburban Philosophy”, looks back at her days as the frontwoman of Cassandra’s Ears which led to the Warners signing, spins good yarns about encounters with Jeff Buckley, Slash, The Cure’s Robert Smith and David Byrne, and muses on being a young and naïve woman in a male-dominated music industry. Its illustrated 220 pages also spend a fair time reflecting on her West Auckland childhood and family life and it’s in those sections where Sportsman of the Year, the book, becomes an affecting piece of work all by itself. (On AudioCulture is an excerpt of the chapter “Neptune and Me”.)

In Love With These Times, by Roger Shepherd (HarperCollins, 2016)

Hellriegel tells a good story about why Cassandra’s Ears was one of a few Dunedin bands of its generation which didn’t get released by Flying Nun. “We sent a demo to Flying Nun and the guy there – it wasn’t Roger Shepherd – said we were ‘fucking awful’ and should give up,” she told Joanna Wane of North & South.

Reading label founder Shepherd’s illuminating and entertaining In Love with These Times: My Life with Flying Nun Records (2016), it’s apparent that the usual rules about getting signed didn’t really apply during the early years. Shepherd, helped in the early days by Doug Hood and Chris Knox, operated largely on slightly woozy instinct when it came to figuring which bands he should release. His book traces how he created – accidentally, then haphazardly – the country’s most enduring indie record label and what it cost him along the way.

His mental health was a factor in his departure from the label in 1997 while working in the London office under the umbrella of Mushroom Records. While it’s a great behind-the-scenes label history, it’s also a book propelled by Shepherd’s self-deprecating humour and his appreciation of the music he released, with frank and funny insights into the personalities of the artists behind it. (Shepherd related his experience of writing his memoir to AudioCulture.)

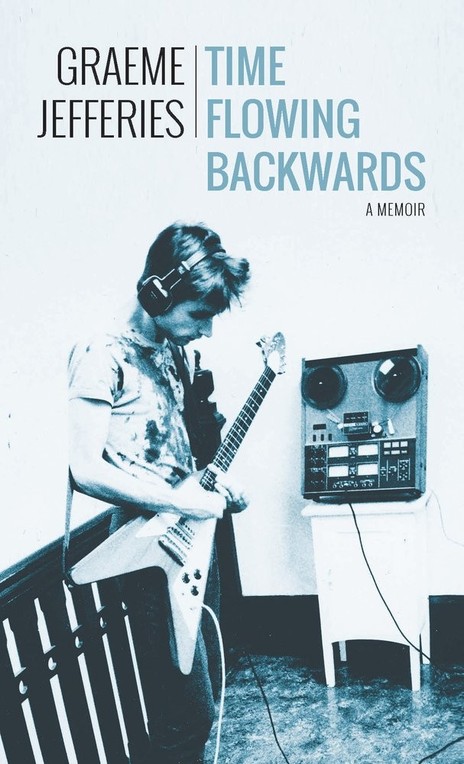

Time Flowing Backwards: a memoir, by Graeme Jefferies (Mosaic Press, 2018)

One of the many artists mentioned with good humour by Shepherd – there was a problem with him humming loudly while helping at the Flying Nun Christchurch office – is Graeme Jefferies of Nocturnal Projections, This Kind of Punishment and The Cakekitchen. Jefferies also remembers his habit getting on his workmates’ nerves in his 2018 autobiography Time Flowing Backwards: A Memoir (Mosaic Press, Canada).

The book starts in the early 90s as Jefferies arrives penniless and clueless in London before finding his feet in Europe and finding a cult following for his lo-fi experimentalism on both sides of the Atlantic. He does go into near-forensic detail about his every recording and tour along the way, with occasional pauses for tales of window-smashing sex, breaking into London squats and family sadness. It eventually loops back to his early outings alongside brother Peter Jefferies in his first two bands, which shared a family tree with Children’s Hour and the Headless Chickens. It’s a book which would have benefitted from an editor but the obsessive detail within is a good match for Jefferies’ singular music.

Goneville, by Nick Bollinger (Awa Press, 2016)

Nick Bollinger’s Goneville (2016) might have been subtitled “A Memoir” on its cover, but inside, the veteran music journalist/author doesn’t necessarily agree with the description. “While much of it concerns music, I would hesitate to call it musicology,” he writes in the preface. “Nor have I set out to write a memoir, although the story starts in the memory.”

Goneville started life as Bollinger’s thesis for a MA in creative writing at Victoria University’s International Institute of Modern Letters. There, the original manuscript won the best-in-class Adam Foundation Prize. But as a book it flies free of its academic beginnings and it’s an often deeply personal memoir set against the period and its music.

It’s also an eyewitness account of how the late 1960s rock counterculture took until the early 1970s to reach New Zealand and how it took hold among the Wellington bands the adolescent Bollinger would sneak out to see – and eventually join.

The first chapter begins with a teenage Bollinger signing on as the bassist in Rough Justice, the soul/R&B outfit led by Rick Bryant, then a junior lecturer in English at Victoria and a man who frequently resembled a human chimney in the era of the buddha stick. Bollinger paints an affectionate but candid portrait of Bryant: at times, he comes across as a soul-singing working drawing for The Big Lebowski. But mainly, yes, Goneville is a memoir and a touching account of music taking over, and defining, Bollinger’s life at an impressionable age.

If I Only Had Time, by John Rowles with Angus Gillies (New Holland, 2012)

His old albums now line the nation’s second-hand shops. So now, given it came out back in 2012, there’s a good chance John Rowles’s autobiography If I Only Had Time can be picked up cheap too. Whatever the cost, it will be worth it because it is a book worth its weight in glitz for the showbiz stories generated by his 50-plus years as a performer, and for the way he tells ‘em (albeit via journalist Angus Gillies, who previously ghosted memoirs by sports stars Justin Marshall, Adam Parore and Matthew Ridge).

It’s a smoothly narrated jetset epic starting in Kawerau, taking his late 1960s hits in the UK (‘If I Only Time’, ‘Hush … Not a Word to Mary’), then shifting to his lucrative residencies in Hawaii and Vegas, only to find himself unable to make his star glow beyond the hotel lounges and his homeland.

Throughout it all, there are surprising stories and tangents, like the one about how he just missed being on the fated Erebus flight. Or the one, from his Hawaiian years, when a guitarist he rejected at an audition for his backing band turned out to be Mark David Chapman, the man who killed John Lennon.

These days, Rowles, in his early seventies and knighted in 2018, is largely retired. But If I Only Had Time is an infectious reminder of how much he enjoyed being in the spotlight for so long.

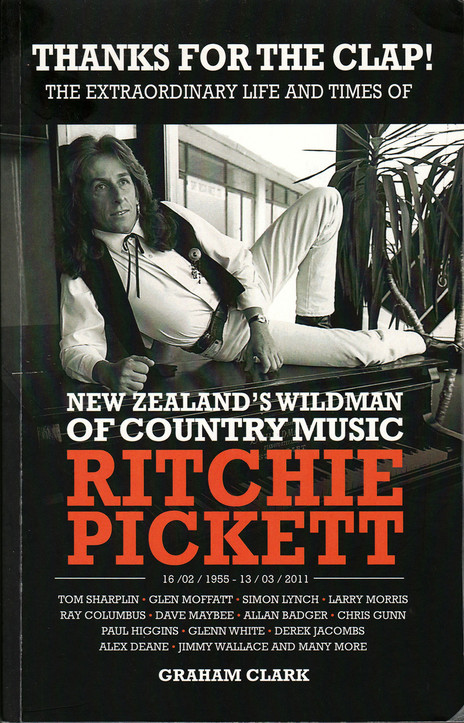

Thanks For The Clap! The Extraordinary Life and Times of New Zealand’s Wildman of Country Music Ritchie Pickett, by Graham Clark (Clark Design, 2017).

If there were prizes for best music memoir title, then surely this 2017 biography deserves a gong: Thanks For The Clap! The Extraordinary Life and Times of New Zealand’s Wildman of Country Music Ritchie Pickett.

That title was a reference to one of the acerbic responses from Ritchie Pickett when he encountered an indifferent audience. Pickett, who died in 2011 aged 56, spent most of his career being a country singer-songwriter and pianist, including performing on the That’s Country television show in the early 80s. In the previous decade, he had done time as a glam and prog-rocker, winding up in Sydney with the band Think before falling into a drug scene with connections to the Mr Asia syndicate.

He returned home to be treated for liver cancer. Recovered, the Morrinsville-raised musician embraced his country roots in an array of bands bearing his name. But his self-destructive side remained, as did his trademark cutting wit.

With just three albums, Pickett has left little in the way of recordings to remember him by. But the book shows he left his mark among those he played with. Musician-author Graham Clark corralled more than 30 of Pickett’s contemporaries to contribute a chapter, all beginning: “I first met Ritchie …”

Among those who added their memories are Larry Morris, onetime producer Ray Columbus (his passage lifted with permission from his own autobiography The Modfather), Simon Lynch, and former bandmates Tom Sharplin, Dave Maybee, and Chris Gunn. It makes for an anecdote-rich portrait of a flawed virtuoso, one who is tellingly described in the book by Alex Deane as “a fascinating collection of people – not all of them nice!”