When New Zealand discovered drugs and androids, androgyny and astronomy, in an environment of excess in the 1970s, cosmic-space-rock was born. An overview written for Rip It Up in 2002.

Space Farm (L-R): Harvey Mann, Billy Williams, and Glen Absolum

Intense hedonism and creative revolution heralded New Zealand’s trip into the 1970s. Psychedelic drugs offered widening vistas to explore; social conventions were being challenged, as were creative ones; and avant-garde tendencies found their way into popular culture.

It was also a period when rock went cosmic, and more and more artists were looking to the stars for inspiration. Neil and Buzz had just landed on the moon, and those with a penchant for astrology believed it to be the dawning of the Age of Aquarius: a new age of peace, love, and spirituality.

An old cliché goes: If you can remember the 60s then you weren’t there. Some have also said New Zealand didn’t really experience the 60s until the 70s were underway. Even pot was scarce in New Zealand in the late 60s, speed scarcer, LSD wouldn’t regularly find its way down under for a few more years, and anything harder was only read about. By 1970, the summer of love had already been and gone in other parts of the world, but hippy culture was only beginning its earnestly bohemian, Pacific incarnation.

Until then, the underground scene in New Zealand had retained an earthy progressiveness that was heavily steeped in the blues. And then there was Hendrix. A one-man, acid-fried, electric revolution that changed the way people thought about the guitar.

What Hendrix had also tapped into was fusion. Music was looking outside its boundaries, causing a collision between the pop, classical and jazz worlds and taking on a new-found free attitude to improvisation and form.

Auckland’s Underdogs, under new leadership from guitar-hero Harvey Mann, had been getting restless working within the restrictions of 12-bar blues. Signalling a more free-form approach, they changed their name to Space Farm. Their weekly gigs at clubs such as Tabla were infamously acid-fuelled events, although some of the chemistry must be attributed to the power-trio line-up of Mann on guitar, Billy Williams on bass, and Glen Absolum on drums.

Space Farm (Zodiac, 1972)

Mann became disillusioned with this lifestyle of excess and by the mid-70s had given it all up for a more spiritual approach. When asked about drugs now, he takes a more pragmatic view of their effects: “Psychedelia is different things to all those who become involved in it, as is music, but at its best psychedelia opened doorways for many of us to realise there was more to life than just surviving on a day-to-day basis.” However, he adds: “Many musicians thought that having a guitar strapped on and a magic smoke of grass gave them a licence to do extended jams for long periods of time, yet they had very little ability in this area and this inevitability ruined it for a lot of people.”

Another legend of excess was Eddie Hansen, who played with heavy acid-rockers, Ticket. Like Mann, Hansen had also become disillusioned with rock’n’roll excess, so – following in the footsteps of Doug Jerebine – they both turned to Krishna for a different sort of enlightenment.

The Living Force album (Atlantic, 1977)

With Ticket and Space Farm no longer functioning, Mann and Hansen teamed up to form the supergroup Living Force, who became notorious for their epic spaced-out jams fuelled by the mantras of Eastern philosophy.

Around this time, a young Alastair Riddell – soon to be launched to stardom with his No.1 hit, ‘Out On The Street’ – had begun his musical apprenticeship with Original Sun. Riddell, who was recruited by his older brother Ron, was only 14 and found himself amid a hotbed of creativity. “The whole of the late 60s, there was such a huge amount of experimentation,” he notes. “So much happened in popular music from about ’66 through to ’72; it was amazing, I don’t think that will happen again. I don’t know why it happened, but it was an exciting time to be playing.”

Alastair Riddell, age 16

Riddell soon established his own group, Orb, moving away from the blues into a more progressive direction. He recalls: “In late 1971, Peter Cuddihy, who was playing bass in the Original Sun, met Paul Crowther and Eddie Rayner [who both went on to be part of Split Enz], and they were interested in similar things. He dragged me off to Mt Albert on a Saturday afternoon, and that was when I met Eddie and Paul. So we started playing a strange mixture of Yes and David Bowie and original material.”

Rayner never really became as much of a drug user as his peers. “I’ve always had an over-sensitivity to drugs of any sort,” he says. “I can’t take two Disprin without going to bed for a week. Let alone mind-altering drugs.”

Riddell had similar views to Rayner and Mann about the defects of drugs on creativity: “I was never a big drug taker, I probably smoked dope more than anything. But you’re also in this kind of milieu of people who are doing other things. So, I would say that drugs were an important part of the whole atmosphere, and if I can plug drugs in a positive way, I think that what they can do is they can take you out of yourself.

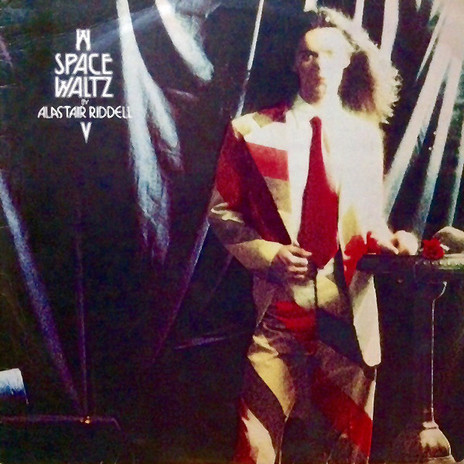

Space Waltz by Alastair Riddell (HMV/EMI, 1975)

“But what happens culturally, and even for individuals, they take a drug, and it does something for them and you think: ‘Wow, this is fantastic’. [And] you mistake the substance for the insight you have, and so you go on taking the substance in the hope that you’ll go on having the insight. Because it’s not actually the substance that does it. That was so common in popular culture and music at the time and maybe that was why there was such a burgeoning of creativity in popular music.”

Space Waltz - the first line-up, without Eddie Rayner. From left: Alastair Riddell, Peter Cuddihy, Greg Clark, Brent Eccles.

As Riddell became increasingly interested in the glitter world of glam rock, Orb evolved into Space Waltz. In stark contrast to the sunny pastoral grooves that had predominated in New Zealand so far, Riddell started taking a more dystopian stance, following Bowie’s example with concept albums about androgynous men from outer space. “I was reading science fiction heavily,” he says. “I was trying to write it. Most of the Space Waltz songs are based on stories and ideas I was tossing around for science fiction. I had an imaginary planet named Telluria. I was really interested in an almost androgynous clone-based future. There’s a kind of sexual ambiguity, there was a droid element in it too, but I was really keen on the idea of cloning and what would happen with genetic engineering.”

After the enormous success of ‘Out On The Street’, Space Waltz moved to Australia, but soon disbanded and Riddell went on to pursue a solo career.

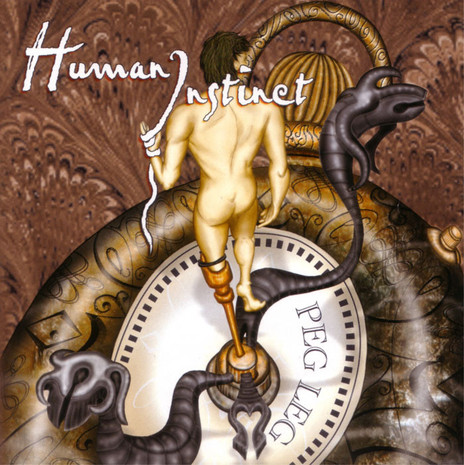

Peg Leg, the unreleased 1975 album by The Human Instinct, eventually issued in 2002 as Peg Leg (the Lost Tapes).

The most successful and hardest rocking New Zealand group of the era was Human Instinct, who recorded six albums – the sixth, Peg Leg, was never released but is soon to be officially issued [ed: it was released on CD in 2002] – and survived two stints in the UK. They were characterised by a rock-solid rhythm section, led by Maurice Greer, who pounded away standing at his customised drum kit, closely followed by fiery bass grooves and a roll call of ace guitarists – most notably Billy TK.

Human Instinct’s raw power can partially be attributed to Greer’s strong work ethic. In the 1950s, at age 14, he had already started playing in working bands, touring up and down the country. Always wanting to give a maximum performance, his only poison was a little vodka, although other members were certainly prone to dabbling.

The Human Instinct: Neil Edwards, Maurice Greer, Billy TK at Club Bo Peep, Durham Lane, Auckland, in the early 1970s

In the late 60s Greer left for England with The Four Fours, who changed their name to Human Instinct to keep up with the harder emerging sounds. They spent two years touring the UK with artists such as Jeff Beck, The Small Faces, Roy Orbison, and Hendrix.

The Human Instinct at Club Bo Beep, Durham Lane, 1970: Larry Waide, Maurice Greer, Billy TK

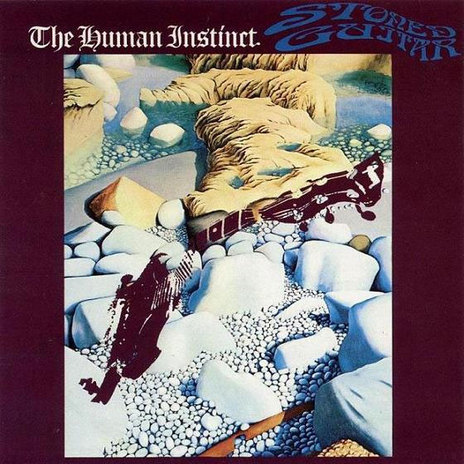

A second trip to London saw them arriving home with a stack of new gear, making them the loudest band in the land. They set about recording some of the toughest licks this country had heard. A batch of songs that Jerebine had recorded in London under the name Jesse Harper became the basis of the first two Instinct albums, Burning Up Years, and the classic Stoned Guitar.

The original Stoned Guitar sleeve, adapated from a work by New Plymouth artist Michael Smither (Pye, 1970)

Stoned Guitar took off in Australia and has since become much sought-after by collectors all over the world (a good condition original pressing can now fetch up to $1000). Towards the end of an Australian tour, TK took some acid and was told in a vision to return to New Zealand to play his own music. Without telling anyone, he boarded a plane the next morning and left the Instinct. He formed Powerhouse, though he briefly returned to record the third Instinct album, Pins in It, which was followed by two more countrified efforts before Greer disbanded the group.

Human Instinct were the last survivors of that era – and certainly the most successful with their space-rock explorations. Recently, Greer has returned to the studio, with TK playing some guitar and Neil Edwards on bass, to record a new Instinct album, which he will tour this summer [2002-2003].

Rayner and Riddell have also been recording again under the name Space Waltz and a new album is on its way.

--

Guitar Aces

Doug Jerebine

Doug Jerebine in London, 1969

Already considered a guitar ace by the early 1960s, he played with The Keil Isles and the Embers before founding the supergroup The Brew, where he had a marked influence on burgeoning legend Harvey Mann. Changing his name to Jesse Harper, he moved to London with Human Instinct, played a few shows with Jeff Beck and recorded an album worth of material said to have impressed Jimi Hendrix. That tape finally saw a belated release in 1993 as Guitar Absolution in the Shade of the Midnight Sun.

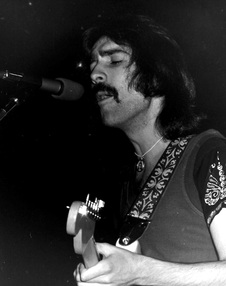

Harvey Mann

Harvey Mann, with the Underdogs

When the same was being said about Clapton in the Northern Hemisphere, it wasn’t uncommon to find graffiti around Auckland proclaiming, “Mann is God”. Ironically, Harvey Mann was never really a fan of Clapton’s guitar playing. He played with The Underdogs and Brew before forming the more experimental Space Farm, allowing him to stretch beyond the limitations of playing 12-bar blues. Taking a more spiritual – less substance-fuelled – approach, he then formed the Krishna-oriented outfit Living Force with Eddie Hansen.

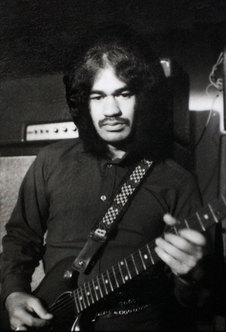

Billy TK

Billy TK with The Human Instinct

Before discovering Hendrix, Billy Te Kahika was already experimenting with feedback and making his own guitar pedals. He left Human Instinct mid-tour in 1972 to form his own group. With Powerhouse he took the spiritual leanings of fusion players Carlos Santana and John McLaughlin, proudly adding his own Māori heritage to the mix. More recently he’s appeared on albums by DLT and King Loser, and at a 1996 Auckland concert he found himself taking all the solos on Bob Marley’s ‘Exodus’ with Santana himself.

Eddie Hansen

Eddie Hansen, Christchurch Town Hall, 1975 - Photo by Kevin Hill

Before Hansen teamed up with Mann for the twin-guitar dream team of Living Force, he had already played in a string of groups including Revival, Challenge, and Ticket. Ticket was New Zealand’s foremost acid band whose spaced-out sets included songs that could go for 45 minutes, a hedonism that Hansen eventually tired of, ditching the band to explore a more spiritual path with Living Force. Having quit drugs, alcohol, and meat, they played even more epic Krishna mantras that went on all afternoon.

--

This article was first published in Rip It Up as “Interstellar Overdrive”, Oct/Nov 2002

Note: This article was written in 2002, anticipating a Human Instinct gig at Java Jive, Auckland, on October 26. Developments since: Doug Jerebine released This is Jesse Harper in 2012, 43 years after it was begun; Human Instinct released Peg Leg (the Lost Tapes) in 2002 and Midnight Sun in 2009: Space Waltz finally returned in 2023 with a few gigs and the album Victory.