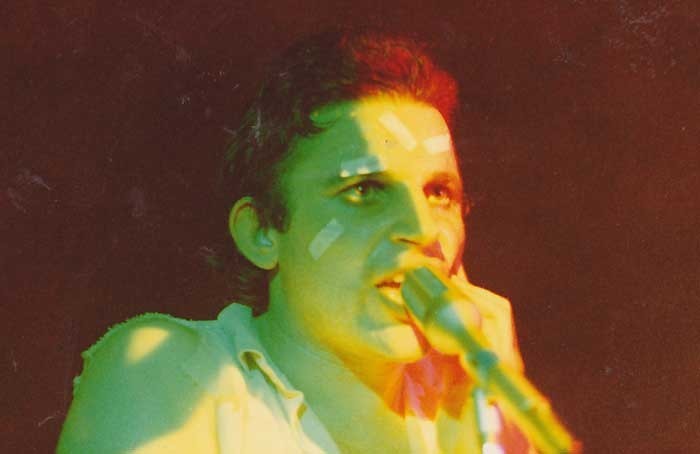

Chris Knox with Toy Love - Photo by Julie Curlette

The following is part one of a conversation between Gareth Shute and Chris Knox from early 2007. Two years later Knox had a stroke which left him with very limited verbal abilities. We are publishing this transcript in full so fans, researchers and writers will have access to his raw reflections on his life in music and better understand Knox’s important role in the New Zealand music scene.

--

I’ll ask you some questions chronologically from the very beginning.

The very beginning! God created …

Were you born in Invercargill or did you just grow up there?

Born and bred in Invercargill.

Usually, you are painted as a music and comic lover early on, but in my mind that makes you sound quite introverted.

God yes I was introverted! In early years, I wasn’t. I didn’t really become neo-introverted until I hit high school. Being an only child, I spent a lot of time by myself. I mucked around on the piano a lot, listened to a lot of music, and both ingested and drew cartoons. I did more of the input than the output when it came to comics. I was lucky in that I had people across the road that actually subscribed to all the Walt Disney comics that were coming out. They’d just read them once then hand them to me and I collected this huge stack of Walt Disney comics. They also used to get the 100-page comics which were black and white reprints of American superheroes and that sort of stuff – basically Superman, Batman, and the Flash.

I listened to as much music as I could possibly do, which was mostly on the radio, because I couldn’t afford records back then. As soon as I could afford to buy records, I started to buy mostly singles by the obvious contenders – The Beatles, Stones, Kinks, that kind of thing.

After school you moved to Dunedin to go to university?

Yeah, I lasted almost a whole year at university before I realised that it wasn’t me and I wasn’t them.

What were you going to study?

Buggered if I know, I was all over the map. I was doing French, English, Phenomenology of Religion, Philosophy. I suppose it’s not all over the map really, is it? Just arts.

“It was a sexual awakening. Well, I’d been awake, but I hadn’t been getting any.”

What was Dunedin like at that point? Was it already a student town?

Yeah it was, we were right in the middle of the whole student thing. I was staying in a hall of residence literally surrounded by students, above, below, left, and right. It was a sexual awakening. Well, I’d been awake, but I hadn’t been getting any. Everything came to pass. I’d lost three stone, just before going to Dunedin I’d grown my hair, I’d got 120 miles away from my parents. It was great. I was surrounded by a whole bunch of people who didn’t want to bully me – that was really cool. I discovered that some girls tolerated me; that some of my albums sounded even better through the stereogram in the hall of residence, because I’d only previously listened to them in mono; that live bands could occasionally be interesting too. There were bugger all when I first got to Dunedin which was in 1970, but I saw Split Enz at the university when they were still “E N D S” and they were in one line across the stage, no drummer.

I saw Highway, they were pretty amazing. They did two gigs in two nights, and I went to both of them. I’d never heard of them. They were just a New Zealand band with really long hair, really long jams, and this one song – ‘Going Down the Road’ or something like that [‘The Ride’ by Highway] – the first night it went for half-an-hour and was really loud and the second night, it went for a bit longer but was really quiet. So that was interesting – “oh, you can do two different things with the same song, woohoo”. So those were the two that really spurred me on in my early years.

How did you first get into music then? Punk music was coming through.

I could fumble around on the piano. I could play the major chords on guitar. I struggled with anything apart from that. I knew I could write songs; I’d been writing them on piano for quite some time before that. So, when punk came along, it was like, “oh, okay, this is just the Troggs sped up”. Those sorts of songs are easy to play. They’ve got a certain angle which has always been in my songs – either about some woman who wouldn’t put out with me or some political situation or something. So that gave me the impetus to get together some friends of mine and say, “why don’t we stop being a cover version band?” – which we had been for a couple of weeks – and write our own songs and do this punky thing. And lo and behold it came to pass.

What covers were you doing?

Probably Beatles, Stones, and Doors. Probably the same sort of thing that Toy Love ended up doing I suppose: Kinks, The Doors, Velvet Underground, Badfinger, Dylan, ‘Yummy Yummy Yummy’, which is a totally underrated song.

How did you meet Alec [Bathgate]?

I was working in a music store for a friend for a fortnight. ‘Neat, Neat, Neat’ by The Damned had just come in, which was the first punk single to hit New Zealand, so I did a little desk stand display for them. These two dishevelled guys walked in. They were younger than me and they turned out to be Mike Dooley and Alec Bathgate – i.e. the drummer and guitarist from The Enemy and later, Toy Love. They were both struggling Fine Arts students. I said I could play bass because we started talking about this punk single. We got together and had a practice together which proved I couldn’t. That I owned a bass, but that was as far it went.

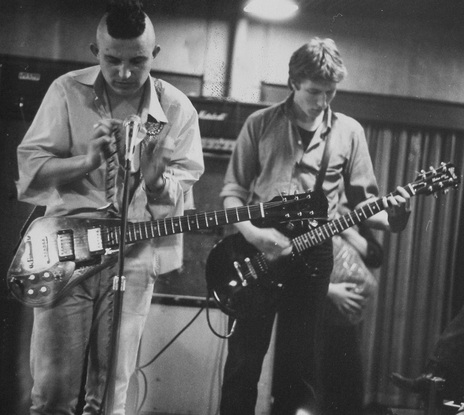

The Enemy: Chris Knox, Mike Dooley, Mick Dawson, Alec Bathgate.

But I had this ridiculous idea that I could write songs, so instead of doing the Stooges and T. Rex covers we were thinking of doing, we went straight into writing songs. As I remember it, within five weeks or a couple of months from actually getting together, we had committed to doing the end of year ball for the art school down there as the sole attraction, so we had to write like hell. We’d written twelve songs by the time it came around. Such was the joy that beheld our musical-virginity-breaking that the crowd made us play them all twice. It took us an hour to get the PA going. Calling it a “PA” is an exaggeration of what we had going and what we had didn’t work, so by the time we started playing, the crowd were ready for anything. But yeah, it went off, and we even got a rave review in Rip It Up for that very first gig. So, it was all downhill from there.

That was the anti-disco rally?

The anti-disco rally indeed.

“I JUST LET ALL MY INHIBITIONS – WHICH I HAD A STACK OF – EVAPORATE IN ONE FELL SWOOP.”

Alec and Mike were quite a bit younger than you?

They were about seven years younger than me from memory. I was 25 and they were 18, but I had a similarly aged bass player – Mick Dawson – who had been my flatmate for a while. He was basically a crazy, English, ex-skinhead, classical guitarist, who I convinced to play bass. Which I think from memory was about four days before the gig. We’d run out of other options on bass, so we said – “Mick, could you do this, just for one night then we can find somebody else?” He was so bloody rapt that we became The Enemy and stayed that way.

Did it take a while to develop your stage persona?

No, it just sorta exploded pretty much fully fledged on that first night. I just let all my inhibitions – which I had a stack of – evaporate in one fell swoop and became the loathsome, pathetic monster that I’m known as now.

What do you think it was that freed you from being the comic nerd you had been?

Well, I’d been practising with drugs and alcohol and sex for some time in order to become a monster of some nature. It had gotten to the point where me and my mates were excluded from quite a few pubs around the place because we were so bloody uproarious and insulting and vile, especially to the musicians whose cover bands we totally detested. So it came pretty naturally to express that onstage.

Doug Hood, Mick Dawson and Chris Knox with The Enemy, probably at The Windsor Castle, Auckland, 1978

Other younger bands started coming through after that and you knew Hamish Kilgour?

The Kilgour brothers were practising in the same practice room that we were using and we were mates with them anyway, more so with Hamish. David, his younger brother, I didn’t know nearly so well. It was obvious from the word go that they were really interesting, so they played at our second gig as The Clean with Peter Gutteridge on bass, and our sound person, Doug Hood, on vocals, which was rather different than the classic Clean line-up. From the beginning they were very cool, even if Doug wrote lyrics like “she’s a dog” which you wouldn’t associate with latter-day Clean. They had something going – the drums and the guitar in particular were really individualistic from the word go. Other than that, there were just a couple of cover bands like London SS – punk-by-numbers sorta guys. Whereas The Clean were like us, all original and just different. We were punkier than The Clean. They were almost like avant-garde R&B, they were weird.

Were you aware of The Same and Bored Games before you moved to Auckland?

Bands like them hadn’t started. They’d heard of us, and I gather Martin [Phillipps] at the very least had tried to get into a gig but failed. I don’t think any of those guys saw us live as The Enemy and we certainly didn’t know anything about them. If they had even started by the time we left – which was halfway through 78 – we had no knowledge of them.

Chris Knox and Alec Bathgate at Auckland University Cafe, 1978.

How did you find Auckland when you first went up there?

Auckland was weird, because we’d been reading Rip It Up and it was talking about all these bands who sounded fantastic. We got up here and we felt they weren’t as good as us. Scavengers, Get Smart, Rooter. They were fun and it was great fun playing at Zwines with them, but we felt we had an edge. Who knows whether it was true or not? It’s good to have that sort of ego at that point in your musical career – to think you’re the best band in the whole damned world.

“Auckland was a trendier scene – people dressed like punks, which they didn’t do in Dunedin.”

But yeah, [Auckland] was a trendier scene – people dressed like punks, which they didn’t do in Dunedin. There was a real antipathy between the punks and the disco kids, which there wasn’t in Dunedin. It was just a much more stratified musical scene, as you can tell from photos of people at Zwines and – for argument’s sake – the people at the Beneficiaries Hall in Dunedin. In the Dunedin photos, yeah, there’ll be a couple of skinny ties, but apart from that most people have got long hair and flares. In photos at Zwines, there were always two guys with long hair and flares right up at the stage, headbanging like mad – they were there every time we played – but aside from that, everybody looked like punks. So, there was that difference.

A few of the Dunedin bands kept that low-key way of dressing?

Down there they are pretty disparaging of trendy Auckland. Were then, still are. I was going to say that it was a matter of pride to be “normal” but it wasn’t even really a matter of pride. It was just like – not even thinking about the sort of things that makes Auckland tick.

So the leather jackets they wore would’ve been just as much to keep out the cold?

To keep out the cold certainly, but it’s true there were certain looks that were favoured, but they tended to be quite behind the times, whereas Auckland was just ever so slightly behind the times.

The Enemy in 1978 - Mick Dawson, Mike Dooley, Alec Bathgate and Chris Knox - Photo by Carol Tippet

How did you do your first recordings?

The first recording we ever did was in Rob Henty’s living room to a four-track, while his family cowered in the kitchen. That was a demo that we sent off, to absolutely no avail. I think our first recording was when Phil Judd looked like he was going to replace Mick Dawson in the band. We did a bunch of two-inch 16-track or eight-track recordings. We just did all our repertoire that we were going to keep from The Enemy and mixed the bass up real loud so Phil could get the bass lines. After that, The Enemy recorded three tracks for a single at – I can’t remember where – but it was with Dave Russell producing, who was the guitarist from the Invaders [“Ray Columbus and”]. He was recording the Scavs as well and he was much, much more interested in the Scavs than he was in us, so the Scavs stuff sounds way better than our three songs and they were never released. Even though we had the artwork all prepared, we just realised – “nah, this sounds like crap”. So that was all The Enemy recorded.

So, your recording career really started in Toy Love? Your very first single ‘Rebel’ was even reviewed in the NME early on. How did that come about?

WEA in the form of Terry Hoag – Terence Hogan – had been sniffing around The Enemy for quite some time. He was dismayed when we broke up but overjoyed when we very quickly – in the beginning of 1979 – became Toy Love, with the addition of a Christchurch female-male duo and adding keyboards to the mix. So, he got WEA to record and release a single, which was ‘Rebel’ and ‘Squeeze’. That was recorded at Mandrill with Glyn Tucker Jr and we were really pleased with that single. We got it while on tour in Hamilton or somewhere. Immediately after the gig we whacked it onto someone’s home stereo following a whole bunch of old 60s singles that had been playing and it held up.

Someone sent a copy over to the NME and Danny Baker wrote a really good review of it. I don’t think it was single of the week – it may have been. He was shocked that such a good couple of songs could come from somewhere as far away as New Zealand. That was really cool because NME was our bible at that point.

Toy Love's 'Rebel' reviewed in NME, October 1979

Was it a conscious decision to move away from punk by adding a keyboard player?

We didn’t want keyboards, but the bass player came with a keyboard player [Jane Walker] and she was really cool and it turned out she had a clavinet, which is a very rhythmic instrument. Its keys are plucked rather than hit, it’s quite a percussive instrument, as made famous on ‘Superstition’ by Stevie Wonder. She was like another guitarist when she was playing that. She had a nasty old organ that sounded great as well, so we could do Doorsy sorta shit and some of the Velvet Underground stuff that had organ on it. It added bass frequencies as well, which was quite nice.

But yeah, we were getting away from the punk scene more to distance ourselves from the violence that was growing up with the boot boys and the butch slags and all that sort of wonderfulness. Zwines was becoming a reasonably dangerous place to go to. All of our gigs had some violence attached. Part of that was me slicing myself I suppose, but I stopped doing that.

Did you think that slicing yourself up stopped you from being attacked by those violent punks? That’s often the story told in things like the Give It A Whirl documentary?

I was seen as being pretty weird, so yeah. People don’t like attacking the weird, because you never quite know what the weird are gonna do. So even though I was little and really mouthy, I got away with murder really. It was grand. We did want to get away from the violent feel so that’s why we picked those two words – Toy and Love – as the most twee words we could think of.

What was it like going back to Dunedin and seeing those young groups started by people like Martin Phillipps and Shayne Carter coming through?

It was really weird going back to Dunedin, because we thought we were really similar to The Enemy but people were saying, “God, you’re playing twice as fast as you used to and you’ve lost that thing that made you great.” “Oh, have we? I think you’re just not used to us, ya little fucks!”

But yeah, there was this bunch of kids who were trying to get into the bars that they weren’t allowed to, so I remember at one gig at The Cook, we opened up the window, because we knew they’d arranged chairs outside, one story down, so they listened to us at a remove. Martin used to come around when we were staying at the Cook house and just sit in the corner and osmose our rockish behaviour. Hardly said a word, but just sorta sat there quietly in a corner, keeping himself to himself, literally just soaked up the atmosphere such as it was. It must’ve been boring as hell.

Martin’s first band, The Same, played with us, from memory. The thing I remember from that was Jeff Batts’ ‘Thalidomide Babies’ which was the best thing they did that night. Then we went to the town hall or somewhere, where Bored Games and some others were playing. They did a version of ‘Pull Down the Shades’, one of our songs. Everybody assembled said “they did it much better than you tired old fucks did it” and we had to agree, because Shayne was about 12 at the time or something and had all the exuberance of youth, whereas I was getting on to about 27 by that stage. Starting to get a bit past it! [Shayne Carter would have been around 15-16 years old at this point].

Dunedin was a mixed blessing, going back there. It was sorta like – “okay, prove yourself, you rather-be-in-Auckland-fuckers”.

Coming up next in part two: Chris Knox discusses forming Tall Dwarfs with Alec Bathgate and starting his own solo career, as well as working with Flying Nun. Part three covers 1990 and onwards.

--